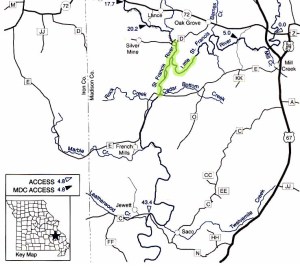

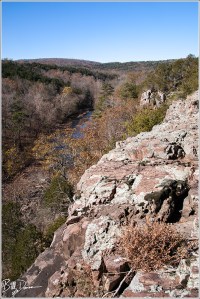

Anyone with a bit of knowledge about the St. Francois River of southeastern Missouri has probably heard of or has even visited the well-known stretch of the Tiemann Shut-ins that create the great series of class 1-3 rapids that experienced kayakers long to ride. The stretch of this river between Millstream Gardens and Silver Mines Recreational Area is one of the most scenic and biodiverse areas of the Show-Me State.

This spring I was turned on to three new-to-me shut-ins in the St. Francois watershed that I should have visited long ago. At first, it was surprising to me that these three geological features are not more well known. However, once I found out a little of the difficulty of getting to these locations, I am now not surprised at all.

The St. Francois Watershed

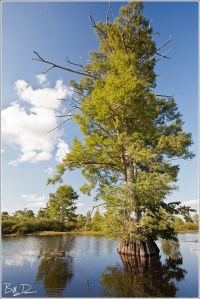

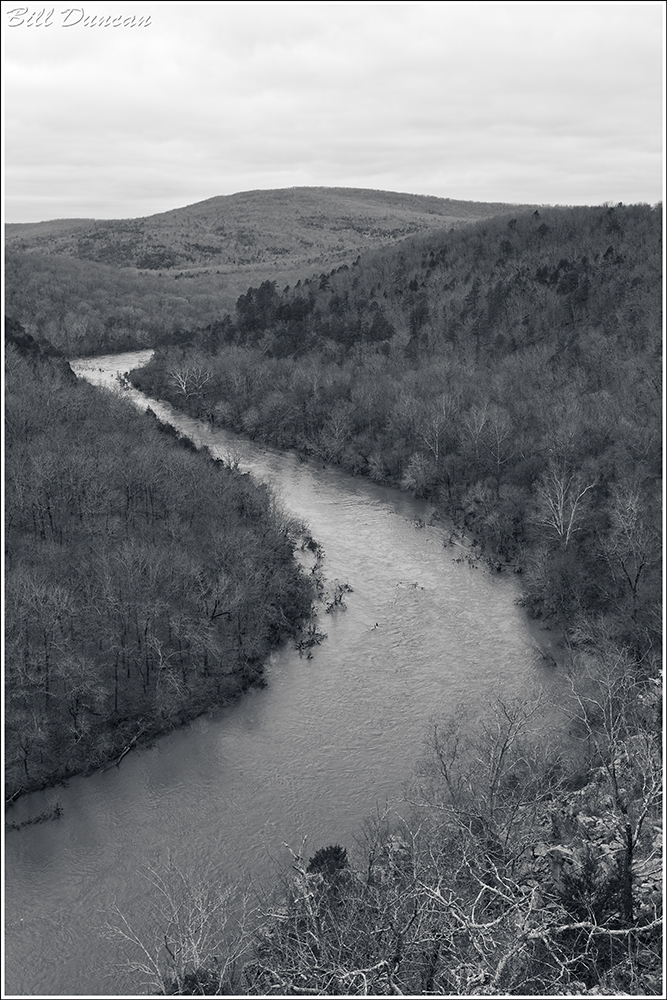

The geological history of the St. Francois River watershed is a tale written in stone, shaped over millions of years by dynamic processes. At its core lies the ancient Ozark Plateau, characterized by its resilient dolomite and limestone bedrock, remnants of a bygone era when shallow seas covered the region. Erosion and uplift sculpted the landscape, carving out rugged hills, steep bluffs, and winding valleys that define the watershed’s topography today.

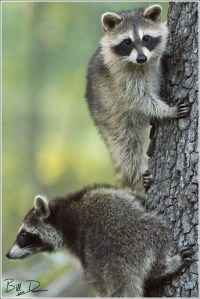

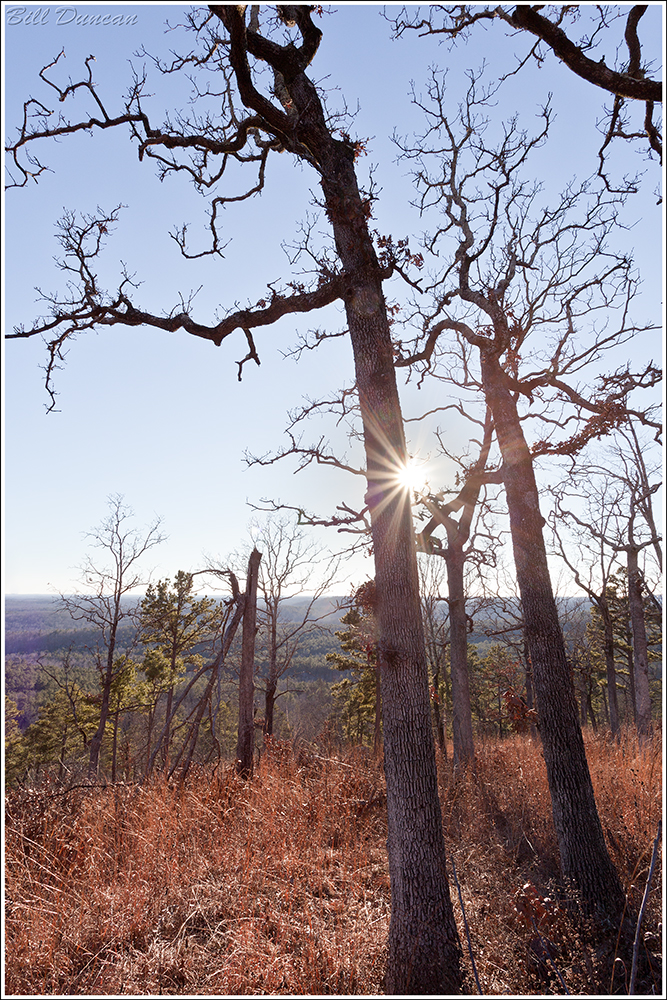

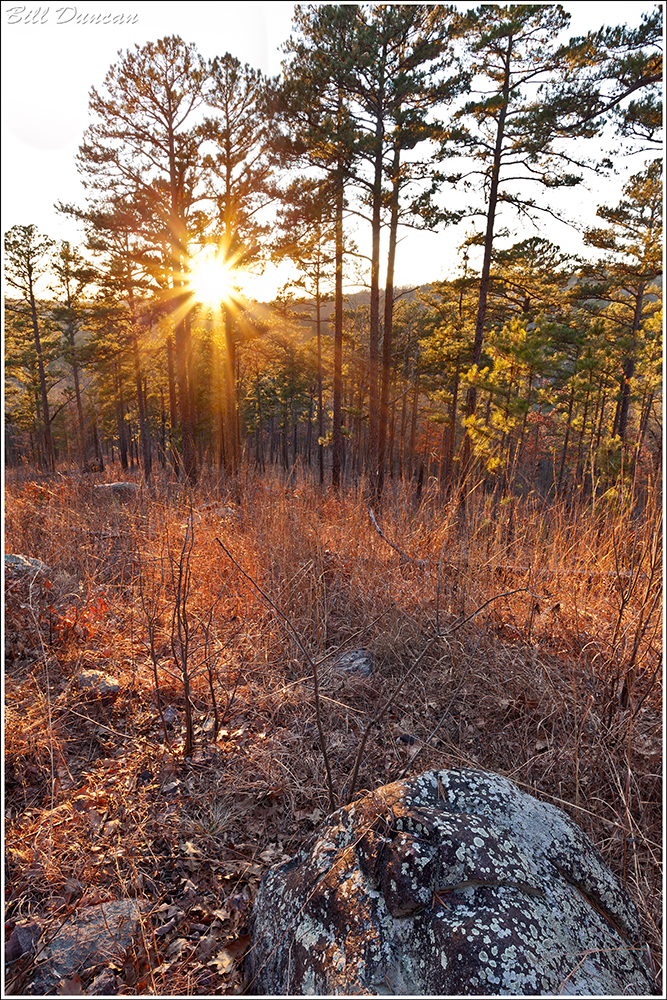

Within the embrace of the St. Francois River watershed thrives a rich tapestry of ecological diversity, harboring a multitude of habitats that support an abundance of plant and animal life. The forested slopes of the Ozarks provide refuge for a myriad of tree species, from towering oaks and hickories to delicate dogwoods and redbuds. Beneath the canopy, a lush understory of ferns, wildflowers, and mosses carpet the forest floor, while clear, spring-fed streams meander through the landscape, sustaining populations of freshwater mussels, fish, and amphibians.

The river itself serves as a lifeline for countless species, offering vital habitat and nourishment along its meandering course. From the elusive Ozark hellbender to the Bald Eagle, the St. Francois River watershed supports a diverse array of wildlife, including many species of conservation concern. Endemic flora and fauna, such as the Ozark chinquapin and the Hine’s emerald dragonfly, find sanctuary within the watershed, highlighting its importance as a stronghold for biodiversity.

About Missouri’s Shut-ins

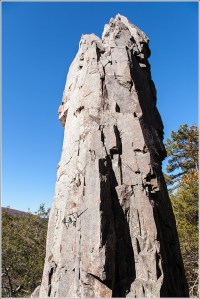

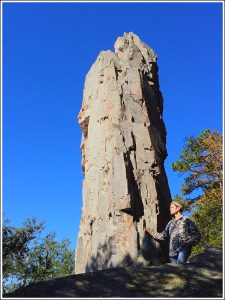

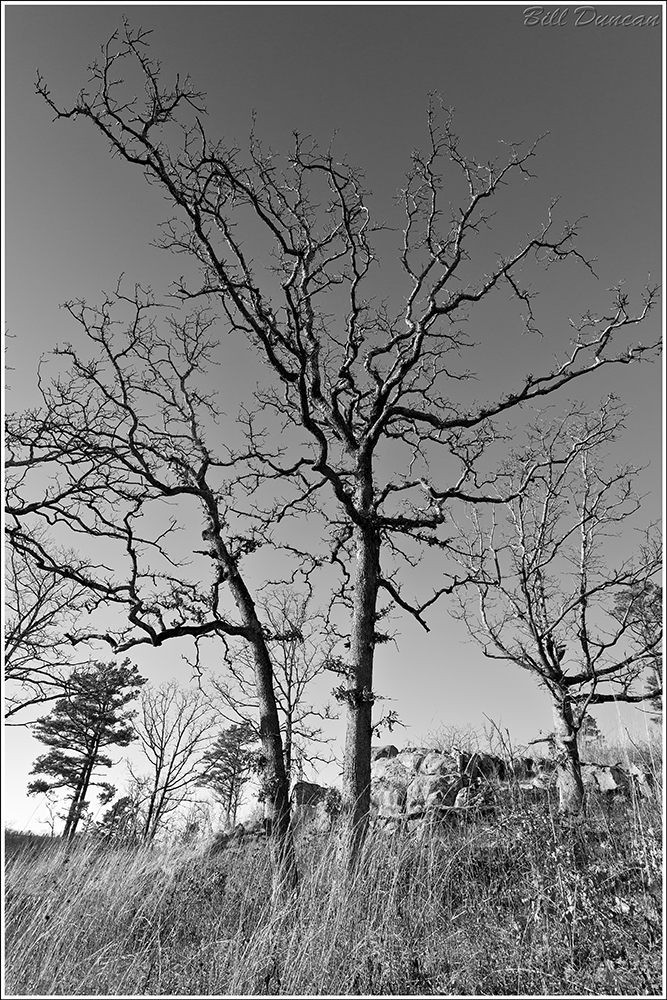

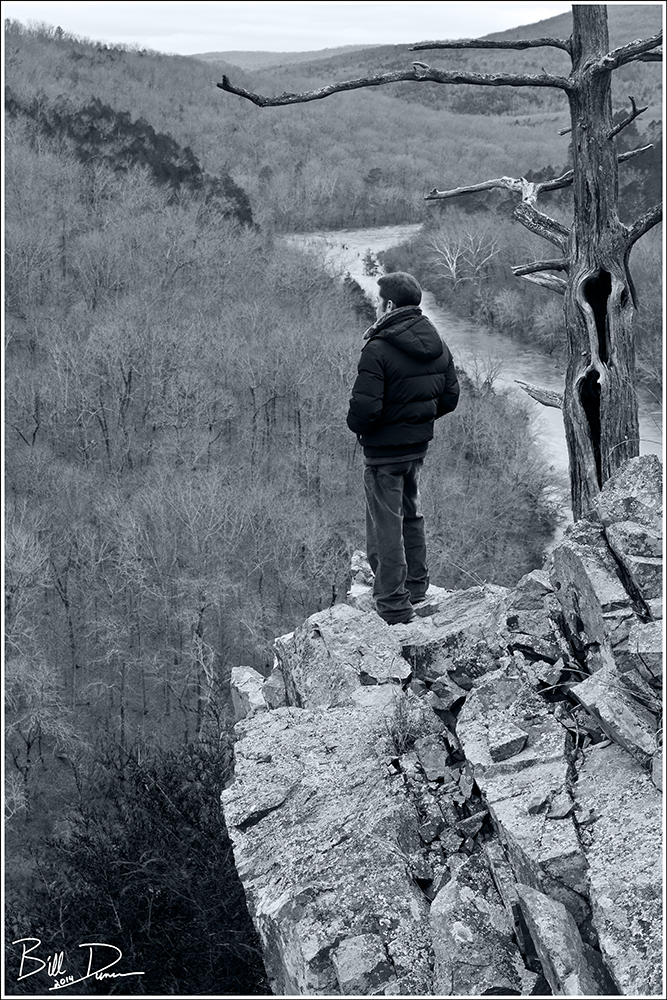

Shut-ins are a testament to the enduring forces of nature. Formed over many thousands of years, these unique rock formations are the result of a complex interplay between water erosion and geological upheaval. The shut-ins, characterized by narrow channels and cascading waterfalls, are formed when swiftly flowing streams encounter resistant igneous bedrock, creating natural barriers that redirect the flow and sculpting the surrounding landscape into breathtaking formations.

Beyond their stunning beauty, shut-ins are also home to a diverse array of flora and fauna. The cool, clear waters of the shut-ins provide a habitat for various aquatic species, including aquatic invertebrates, freshwater mussels and fish. Along the rocky banks, towering hardwood forests thrive, offering refuge to an abundance of wildlife, from songbirds to white-tailed deer. The unique microclimate created by the shut-ins supports a rich tapestry of plant life, including rare species adapted to the harsh conditions of the rocky terrain.

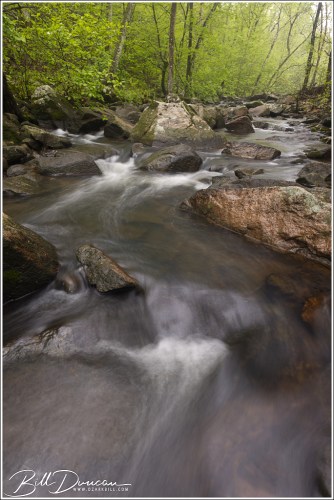

Upper Stouts Creek Shut-ins

One of the main feeding branches of the St. Francois River, Stouts Creek contains a number of picturesque shut-ins. Casey and I had noted this particular one driving by for years but had never made the stop. We had to trespass a little to get our shots, but the folks who own this property are, theoretically at least, supposed to be inclined to forgive those who trespass. We spent just a few minutes here and were in and out without incident.

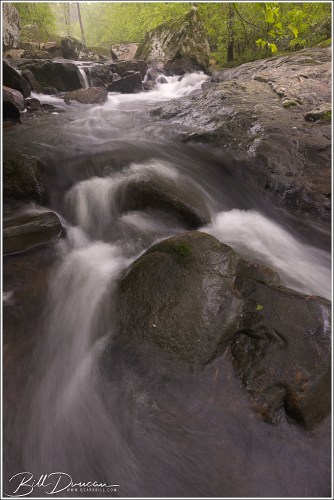

Turkey Creek Shut-ins

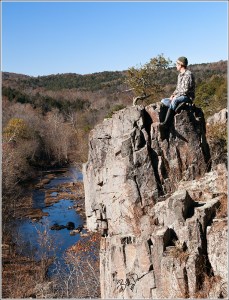

Flowing from the north, Turkey Creek empties its contents into the east side of the St. Francois River, just upriver from the historic Silvermines Dam. Getting to the Turkey Creek Shut-ins requires either a treacherous hike along the creek from the confluence, or a slightly less arduous bushwhack up and over a highland to the sight of the more picturesque parts of the shut-ins. Taking the easier way means missing portions of the shut-ins but will also result in fewer potential run-ins with cottonmouth snakes and ankle-snapping rocks.

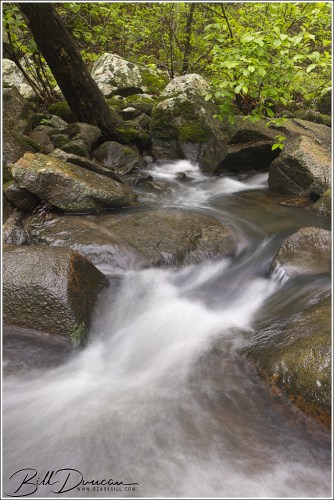

Mud Creek Shut-ins

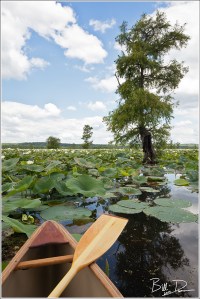

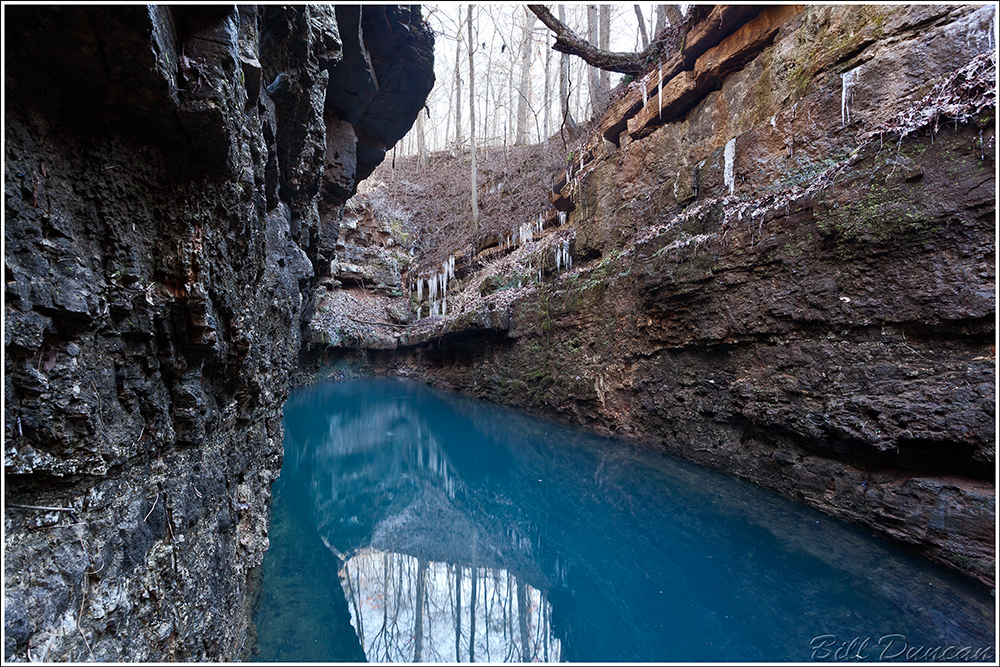

Mud Creek Shut-ins are definitely one of the most memorable shut-ins that I have had the pleasure to visit – not only because of their classic St. Francois Mountain beauty, but due to my story in reaching them. As is the case with Turkey Creek Shut-ins, these shut-ins can be reached by paddling the St. Francois River. However, I doubt my kayak skills would service safe passage across the class-3 rapids of this stretch of the river, especially while carrying expensive camera gear.

The next best option? Footing it across. I began this trek from the parking lot of the Silvermines Recreational Area. In times of high water, the low footbridge across the St. Francois River can be underwater, so I recommend parking on the north side of the river and paying the ridiculous $5.00 to park your car for a few hours.

From the parking area, I took the “trail” that runs upstream along the north side of the river until I got to the namesake mines. From here, it was steep climbing until I eventually ran into an old two-track that allowed for some switch-backing until I eventually rose from the river’s ravine into a more upland forest. Although the topology here was more manageable, fallen trees were everywhere, presumably from strong storms of recent years. The bushwhacking got frustrating, especially with the need to eat a spider or two every five to ten steps! Using my GPS, I kept the river to my right side and generally headed to the northeast to where Mud Creek meets the St. Francois. I should have headed much further to the north, but I kept finding myself heading back into the boulder-strewn ravine of the river. Eventually, I learned my lesson and rose to the highest elevation possible and made a direct line to where the GPS told me the confluence would be. Finally arriving, I realized I was then facing the hurdle of heading back down the ravine to the confluence. I could hear rushing water from the east and the north, shut-ins along the river and creek, respectively. I chose my point to descend into the ravine, not knowing if this would take me to sheer cliffs that would force me back up to try again. I eventually stumbled into the relatively small river bank that was thick with twenty foot tall alder and witch-hazel thickets.

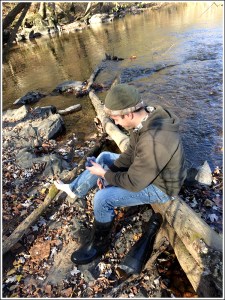

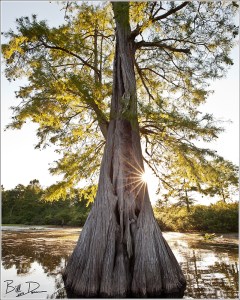

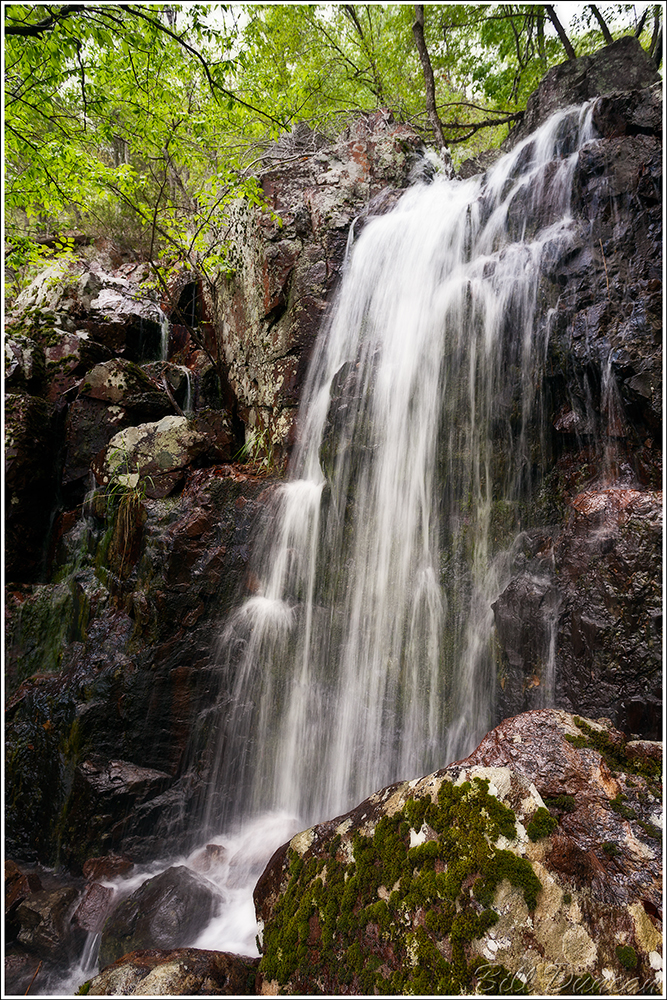

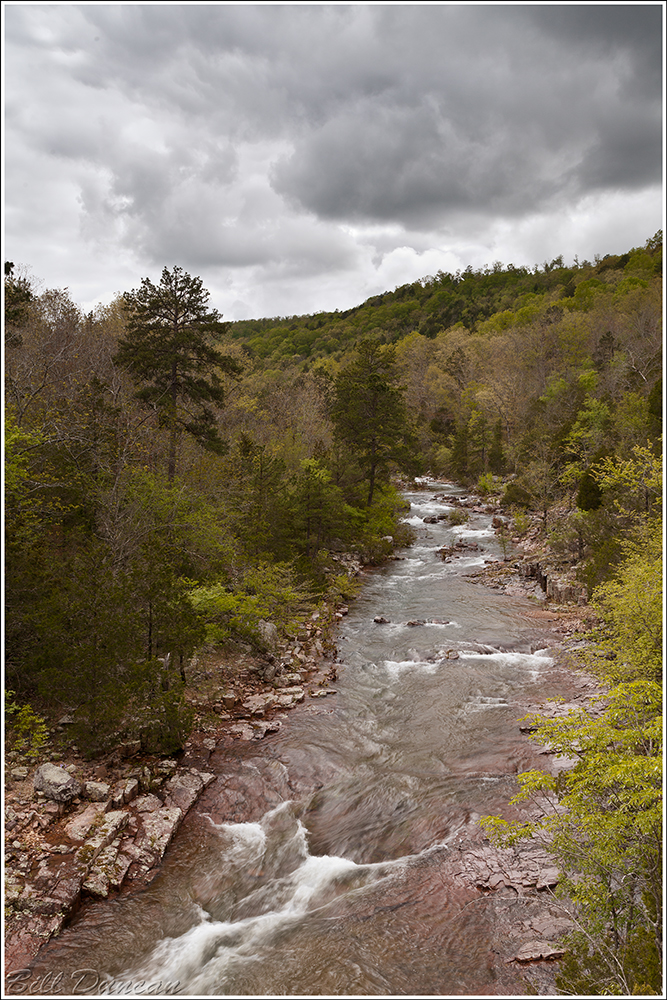

Clearing these thickets, with water halfway up my wellies (I got my first pair of Gumleaf boots recently, so I can no longer call these muck boots), I was finally able to see the confluence. Navigating around huge boulders, I began clambering up Mud Creek and almost immediately came upon the nicest waterfall of these shut-ins. About this time, the sky began to darken. Most of my trek to this point was in mostly sunny skies, making me wonder if the overcast skies forecasted for this afternoon where ever going to happen. Now I was hearing thunder and watching dark skies closing in quickly from the west.

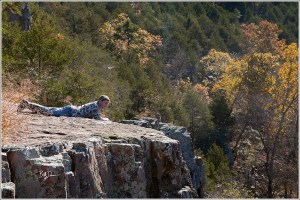

I realized I probably had limited rain-free time with the shut-ins so I got to work, moving myself and my gear from one point of interest to the next upstream. This type of landscape photography is not for the faint of heart! Due to the sharp sides of the ravine, I was forced to cross the creek several times, negotiating deep pools, fast-moving water and slippery rocks. On several occasions, I used my tripod as an extra set of legs, helping me stabilize myself while crossing the creek.

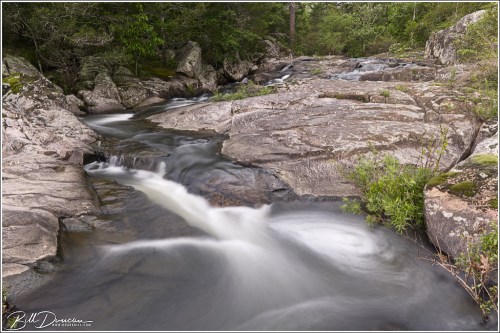

Getting about a half mile upstream from the confluence, the shut-ins widened, opening up to large sections of exposed granite. It was around here that I decided the storm was not going to pass me by, but come right down on me. The thunder was getting closer and more frequent. I put my camera bodies and lenses into individual Ziplock bags and put the rain cover over my bag just when the sky opened up with torrential rains. It was then that I realized I was on the wrong side of the creek to get back to where I needed to be. I also sensed the waters in Mud Creek were starting to rise. The opposite side of the creek this far upstream looked like near-vertical cliffs, but I knew I probably did not have time to head back downstream to a point where I made the crossing earlier. I found the closet point to make a relatively safe crossing and found myself with just a few feet between the steep rise of the ravine and the creek that seemed to be increasing inch by inch. I found some handholds and started climbing. Spiders be damned!

I climbed as carefully as possible, making progress while the rain came down in sheets and lighting danced across the sky directly above me. In five to ten minutes I made it up the approximately 400 feet of increased elevation and reached the top of the ravine. Not liking the idea of clambering down the opposite side of the ravine to get back to the mines, I decided a better route back would be to stay in the uplands and head north to Highway D to get back to my car. That was another two-mile bushwhack, back through the fallen trees, my wellies filling up with rain water, and limited visibility. I eventually made it to the road, finding my way safely back to my car. Not wanting to ruin my seat with my soaking wet cloths and not having a dry change of cloths, I striped to my boxer-briefs, put a towel down on my seat and drove the two-hours home. Thankfully I did nothing to raise the attention of any authorities on the way. 😉

I’d Like to thank Casey Galvin, Kathy Bildner and midwesthiker.com for the information that helped me reach these fantastic locations!