"What a thousand acres of Silphiums looked like when they tickled the bellies of the buffalo is a question never again to be answered, and perhaps not even asked." -Aldo Leopold

On a crisp and beautiful autumn morning this past Halloween, the WGNSS Nature Photo Group group enjoyed the rare occasion of visiting a relatively close St. Louis County location. Part of the St. Louis County Park system, Lone Elk Park has contained herds of elk and bison in some fashion since the original introduction in 1948. This is a beloved park that offers visitors up close looks at bison, elk, deer and other wildlife. Because of the constant visitors, the animals have no fear of humans and, therefore, are an easy subject for the nature photographer.

Due to the cooperative nature of these subjects, a long telephoto lens, typically needed for wildlife photography is not required here. However, it is a good idea to give these animals their space and use common sense to keep the proper safe distance or remain in your vehicle while photographing here. Always be aware of your surroundings and photograph in a group when possible.

I recommend a mid-range telephoto focal length – a zoom lens in the neighborhood of 100-400 mm is an ideal choice. Depending on available light, a support like a tripod or monopod may be needed. However, with modern cameras and their ability to provide acceptable results at high sensitivities, handholding is usually a viable option.

Because this is a nearby location, Lone Elk Park is a great spot to practice with wildlife while building a portfolio of a variety of images. Plan to visit during every season to include the greens of summer, the warm backgrounds associated with autumn and the snows (when available) of winter. Multiple visits will allow for photographing these animals at different life stages, such as when bull elk are in velvet in the summer or while bugling during the autumn rut. From time to time photographers have also been able to capture birthing of bison and elk and the subsequent play of the growing young. I hope to visit this location more frequently in the future.

Here are a few other images I took on this visit.

These photos were taken on a WGNSS Nature Photography Group field trip into the St. Francois Mountains in early June, 2019.

Along with a couple of female eastern collared lizards, we found quite a few other herps of interest.

These lizards are really great photographic subjects. They are relatively easy to photograph, allowing for watching while they bask in the sunlight of a clear day without much manipulation or interference necessary.

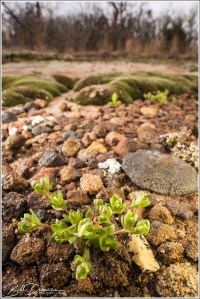

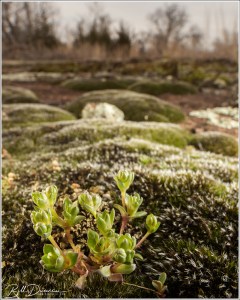

The WGNSS Nature Photography Group headed west early on a lovely day in early April with hopes of finding one of Missouri’s rarest plants – Geocarpon minimum, commonly referred to as tinytim, or earth-fruit. Geocarpon minimum (C=10) is a plant in a monotypic genus known for its diminutive size and rare status. It is listed as federally threatened and as endangered by the state of Missouri. The primary reason for its relative scarcity is its habitat needs; G. minimum requires sandstone glade habitats in Missouri as well as saline “slick spots” where it typically occurs in Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas. A fine balance must be the goal for managers of these areas. Competition and shading by native or exotic competitors is the primary limiting factor of this species and therefore, continuous disturbance is necessary for its continued success.

This plant’s life cycle is short, lasting only 3-6 weeks. Our objective was finding these plants in flower, but there were no guarantees we would find them flowering, or find them at all. Our first and primary hope for finding these plants was at Bona (pronounced Bonnie) Glade Natural Area. Here, our botany leaders, Casey Galvin, John Oliver, and Steve Turner showed us the microhabitat in which to find the plants and were able to point at the first few plants we found. With search images in mind, the group spread out and found the plants throughout the area. Better yet, we found the population in the early stages of flowering! As you can see in the accompanying photos, these are perfect subjects for the macro/micro lens.

After grabbing a late lunch together, a few of us decided to return to Bona Glade. Ted MacRae and I were unsatisfied with earlier images we had taken with our Laowa 15 mm macro lens and we were eager to improve the photos using this specialty lens that, when used successfully, can showcase the plant within its specific habitat.

We photographed the plant on the couple of substrates that we found it on and in the various stages of its development.

Finding and photographing this plant was a long-held goal of mine. It was a very special day spent with friends and newfound acquaintances. I am thankful for those who helped us find this plant and spent time with us. Hopefully future WGNSS members will continue to find tinytim in its Missouri homes for decades to come.

It’s been quite some time since I’ve shared a blog post. This has primarily been due to being in a residence move that is seemingly never going to end. But, I have been finding time here and there to make new images and even get some post-processing done. I have switched themes in this blog, picking a theme that should allow me to create a “portfolio” page to showcase my stronger photos. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to figure out how to do this in WordPress. So I have not gotten far in this endeavor.

My goal is to post more frequently, just to share photos. There may not be a lot of accompanying text, but will depend on the subjects, my amount of free-time and my mood.

The images in this post were taken back in April of 2019 during a WGNSS Nature Photo Group outing to Dunn Ranch Prairie. This visit was close to the end of the lekking period and was the latest date that the MDC was keeping the blind open. This was different than our previous visit when we visited in the earlier part of the season and had pros and cons associated.

Visiting the lek later in the season created better chances for better light (clear skies) and warmer weather. However, what we didn’t expect was that the females typically choose the dominant males to copulate with in the earlier days of the season and will often be nesting come the later days of the lekking season. This is what we had found during this visit. We did not see a single hen during this visit.

Because there were no hens to compete for, the males had no heart for the competition. We had very few opportunities to photograph the action we had witnessed during our first visit to the lek two years prior.

The light, however, was spectacular – we had no reason to complain and we all made memorable portrait style photos of these birds booming, dancing and cackling.

Never a disappointment, hopefully this Missouri population somehow continues to hang on so that WGNSS members can continue to enjoy this spectacle in Missouri.

-OZB

In December, 2018 the WGNSS Nature Photography Group met at Riverlands Migratory Bird Sanctuary with hopes of making some memorable images of our giant white residents that spend their winters here. Trumpeter and Tundra Swans will spend their evenings at roost in the bodies of water at RMBS and will then typically leave to forage in surrounding agricultural fields, picking up the wasted grain from harvest.

A good strategy for placing yourself in the most appropriate position for making photographs of these birds is to pay attention to the direction of the sun. If the birds are found in Ellis Bay during the golden hours of morning light (during winter in St. Louis, this can be up to three hours after sunrise), then getting close to the shore with the sun behind you can produce some satisfactory results. Try getting closer to the ground and shooting the birds from a low angle. This will give your photographs an eye-to-eye perspective that is a much more intimate view into the birds’ world. Shooting at low angles will also tend to provide a more pleasing, out-of-focus background to your subject that will cause the bird to appear to be larger than life. We photographed both species of swan as they lounged in Ellis Bay for the first couple hours of the morning. Can you pick which is the Tundra and which is the Trumpeter Swan in these first two images?

We then moved on to another place within the refuge that the Swans can often be found on winter mornings. At Heron Pond, these birds are typically too far away from the observation areas to get closeup photographs while roosting. However, the patient photographer on the ready can often be rewarded by standing and waiting around. During this morning, the Swans were a tad tardy in lifting out of Heron Pond, so our group was in the right place at the right time. Getting proper positioning with the angle of the sun is a bit more difficult here in the morning but is still critical. We placed ourselves in the best places available on this busy morning and took advantage of the swans as they left the pond, which often flew right over our heads.

Photographing these mostly bright-white birds on a bright sunny day is not necessarily simple. While on the ground or the waters of the bay, it is common to have the camera’s light meter expose for the darker and more prominent background. This will often lead to the white feathers of the birds being overexposed. Remember to check the histogram of your camera and use the “blinkies” while reviewing your images to ensure you are not clipping your whites. If this is the case, make the proper adjustments to your exposure. Saving your whites may result in your blacks and shadows being bunched up at the other end of the histogram. Since the big white bird is your subject of concern, this should be nothing to worry about.

Changing directions and the angle of sunlight are challenging for proper exposure. Get as close as you can in the field – much can be recovered in post-processing.

Shooting these large birds in flight presents a different set of challenges. Although these birds move relatively slower than most other birds during flight, the photographer will still want a relatively fast shutter speed. This is particularly true the closer you are to your subject. I recommend no slower than 1/1000 of a second. Start at this setting and increase shutter speed if you notice blurring or softness to your image due to subject movement. As these birds get closer during flight, they will naturally fill more of your frame, thereby increasing the number of pixels seeing the bright white values. This can often lead to a case of the camera’s meter overcompensating, thereby causing an underexposed image. In this case, the birds may come out looking grey instead of white and the black colorations of their feet and faces will be much too dark and lack sufficient details.

In the above image, a swan can be seen with a significantly crooked neck. I typically see one or two birds with this condition every season. I do not know how it affects the birds or what their ultimate fates may be.

In the case of constant sunny skies, fully manual exposure settings are most called for. Here I will present a good starting point for setting the exposure for capturing swans in flight. Shutter speed – As I mentioned earlier, start with a minimum of 1/1000 sec. This may likely be too slow to capture a sharp image, depending on what position the bird’s wings were captured. Often, shutter speeds of up to 1/2500 sec or higher might be necessary. Aperture – This will depend on how close you are to the swan. Remember, these are large birds and when shooting at a profile there is a lot of distance from wingtip to wingtip. If the bird is significantly close, or if you have multiple birds in the frame, you will be unlikely to capture the entire subject(s) in critical focus if shooting wide open. I recommend no wider than ƒ/5.6 – you may need to stop down significantly smaller. However, always remember that getting the animal’s eye in sharp focus is critical. Many images will work fine if other parts of the bird are not in critical focus. ISO – Remembering that photography is a compromise, shooting at a fast shutter speed and smaller apertures might require that a higher ISO value be needed to obtain the proper exposure. Several latest digital camera models have a useful “auto ISO” setting. I know, technically this is not fully manual, but ISO does not necessarily have the input it once did. Know the highest ISO setting for your camera that you are comfortable with and don’t be afraid to shoot there. This will vary by camera model and by the photographer’s taste.

Here is a photo of “crooked neck” as it flew directly over my head. In cases like this a telephoto-zoom lens is really beneficial for capturing birds in flight.

The majority of this material was originally published in Nature Notes (The Journal of the Webster Groves Nature Study Society) February 2019, Vol. 91, No. 2.

-OZB

Seven of us made the long drive to our destination on the morning of the 23rd . The week of

Thanksgiving can be an excellent choice for visiting Loess Bluff NWR, but always depends on the

weather. We were a bit concerned with the early cold snap our region experienced this autumn.

However, in the week or so preceding the trip, the weather warmed so we were not hampered by ice

that can completely cover the shallow waters of the wetlands. Having open water affords very close

views of our photographic subjects and the primary reason we drove such a distance – the blizzard.

Typically, one million to two million Snow Geese will make this location a stop over during spring

and autumn migration and numbers of over 500,000 birds on a single count are not uncommon.

During our visit, the official counts were slightly over 100,000 birds, but the feeling with the group

was that this was grossly underestimated.

If conditions allow, getting the moon behind the Snow Geese can make a nice composition.

On our first day of the trip we were faced with mostly cloudy weather. As I told the group, this provides an opportunity to more easily try panning motion shots like the one pictured below. This is not my most successful attempt at such an image, but I wanted to share it here to demonstrate the multitude of opportunities for a diversity of photos to be made.

Snow Geese are not the only subjects that make this trip worthwhile. The refuge also provides

important habitat for birds such as Bald Eagles, sparrows, a variety of ducks and wading birds, as

well as mammals like white-tailed deer and muskrats. On our initial entry to the park, Dave and Bill

found a Merlin on a relatively good perch above the road. We spent some time photographing the

bird, but regretted that the rest off our party were on the other side of the refuge and would not

likely be able to get the looks we did. Fortunately, a Merlin – likely the same bird, was spotted on

our second day and was viewable by all.

With subjects in the hundreds of thousands to the millions, making a purposeful image can be challenging. It is quite natural to want to shoot at everything that moves, but try and focus. Finding smaller action scenes is one way the photographer can focus on the individuals and their stories that make up the grander scheme.

Although we experienced skies with periods of heavy overcast, we were presented with fantastic

sunsets on both days. Being able to make the birds part of the story made these images all the more special.

The WGNSS Photo Group is committed to an overnight trip to this and similar locations within the Midwest on Thanksgiving week. If you’d like to join us next year, please let me know!

-OZB

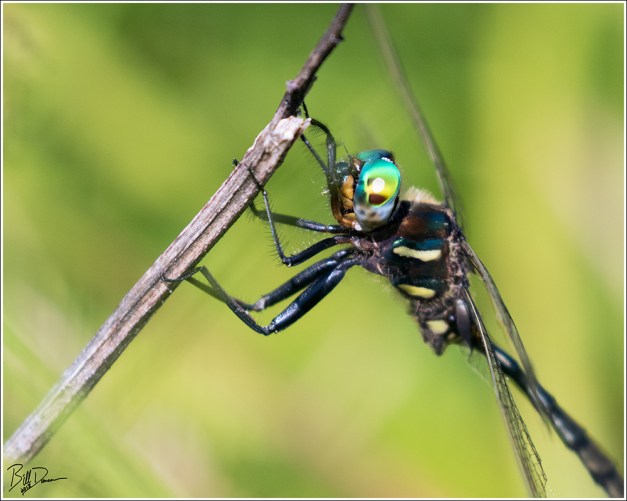

Ever since I heard that a number of newly identified populations had been discovered in Missouri, I have been wanting to find the Hine’s Emerald Dragonfly (Somatochlora hineana). I’ve gone a time or two on my own in previous years, but without specific knowledge on the where’s and when’s to find the flying adults. On June 16th, 2018, the Webster Groves Nature Study Society’s (WGNSS) Nature Photography Group headed to what might be the largest population of this species in the state. Thanks to WGNSS member and photographer, Casey Galvin, we were allowed access to a privately held farm in Dent County, MO that holds this population.

So, what is a Hine’s Emerald Dragonfly and what distinguishes them from the other 24 or so species in the Stomatochlora genus, or the “striped emeralds”? The above photo shows these distinguishing characteristics. Beyond the obvious emerald green eyes that all of the striped emeralds possess is the pair of yellow thoracic stripes on the sides of this species. Another and more diagnostic is the particulars of the genitalia. Using a good field guide will easily allow you to come to a species.

Currently on the endangered species list, S. hineana was thought extinct as late as the mid 1900’s. Current populations of this species are now known from the states of Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan and Missouri. Current population estimates indicate that there are approximately 30,000 individuals in the world. About 20,000 of these are believed to be in the species stronghold of Door County, WI. Like many of the striped emeralds, S. hineana has specific habitat requirements. The preferred habitat for this species is fens and sedge meadows overlying dolomite bedrock. Habitat loss, pesticide use and changes in ground water are identified risk factors affecting the Hine’s Emerald.

Like many dragonflies, S. hineana is a sun-lover, active in the early parts of a June morning before things get too hot and he finds a hidden perch. Until then the males are airborne, patrolling their territory in the hopes of finding a female or a male to chase away. The photographer need be patient and wait for the opportunity when the insect stops to hover in the same general place. This is the split-second opportunity that you wait for. The problem is that autofocus is of little to no help. I primarily used manual focus on the in-flight shots.

There were plenty of opportunities for the patient photographer and observer. Often, an individual would fly so close to the lens we were sure it would use it as a perch. At these distances any movement by the dragonfly would throw it completely out of focus, so the photographer is looking for the sweet spot – close enough to be large in the frame, but far enough to enable tracking.

It was such a thrill to finally be able to meet these guys. With this location and up to 20 others, it is nice to know that Missouri is home to such a rare gem. Hopefully it will remain so.