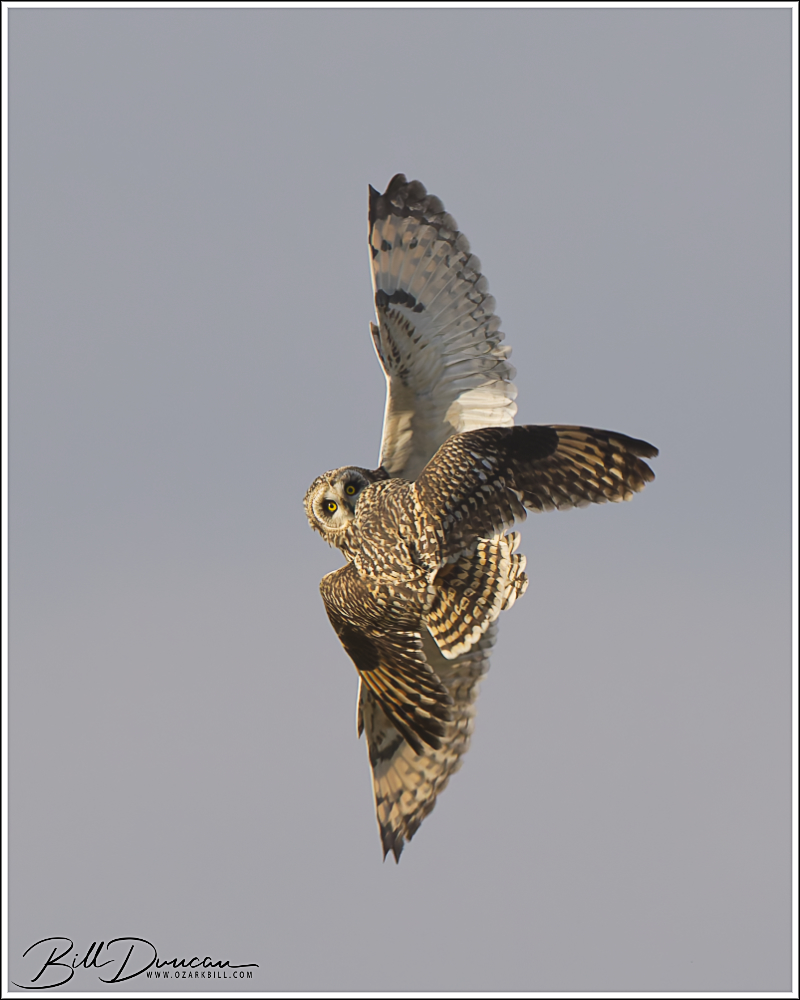

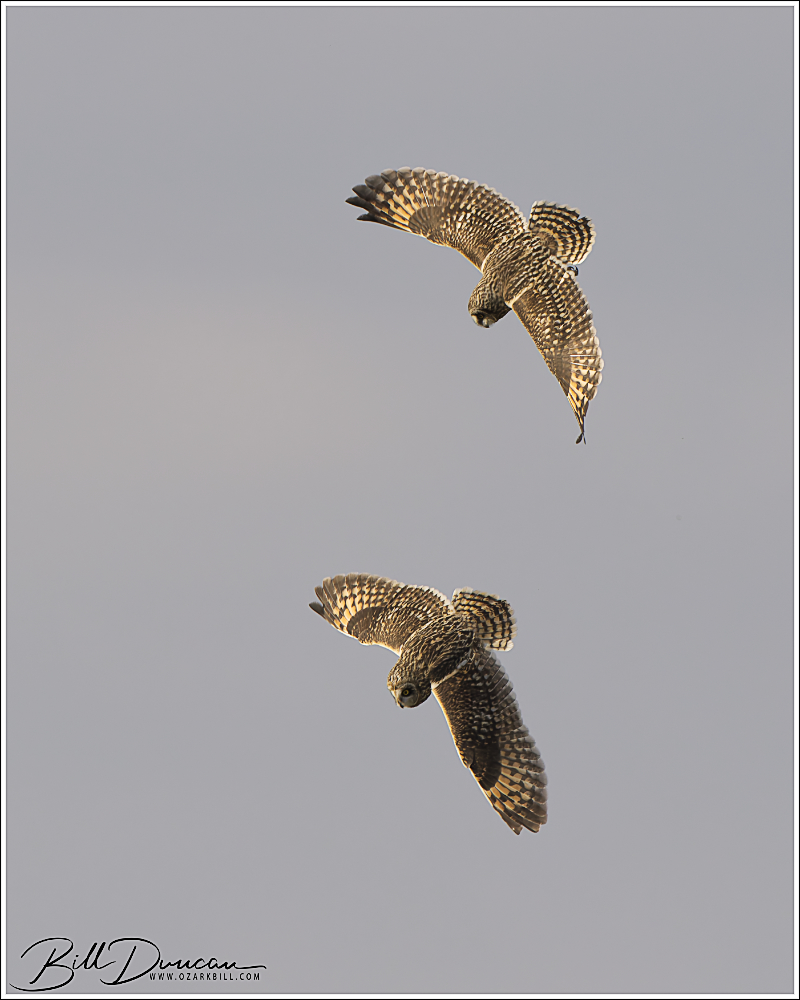

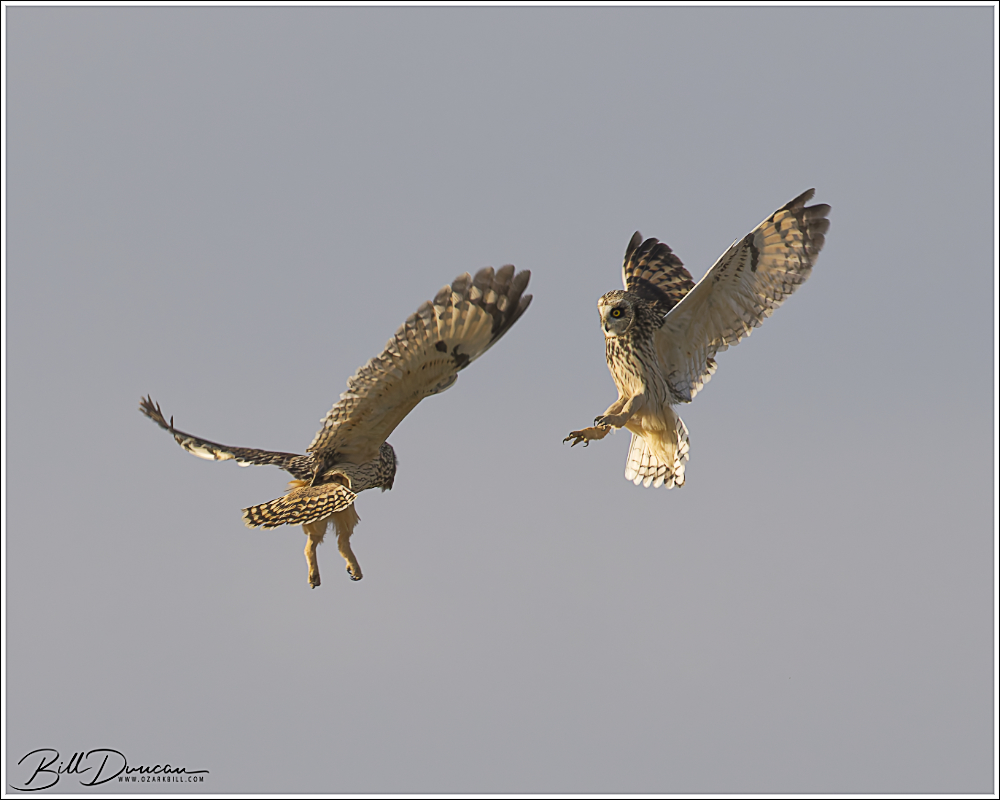

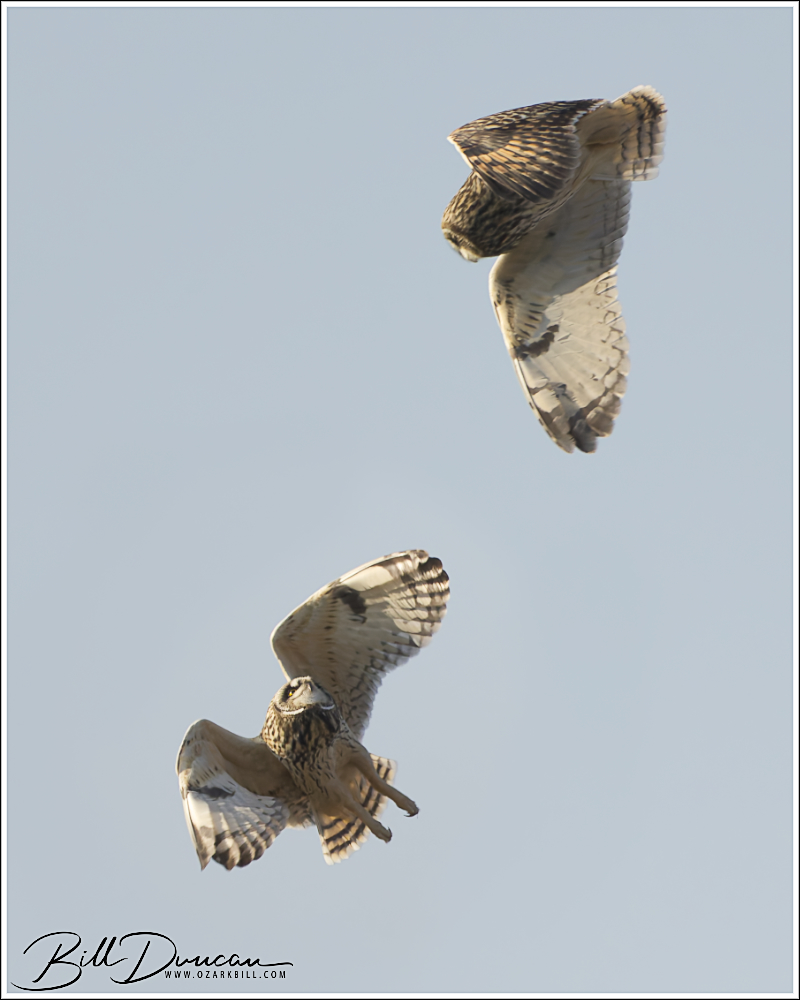

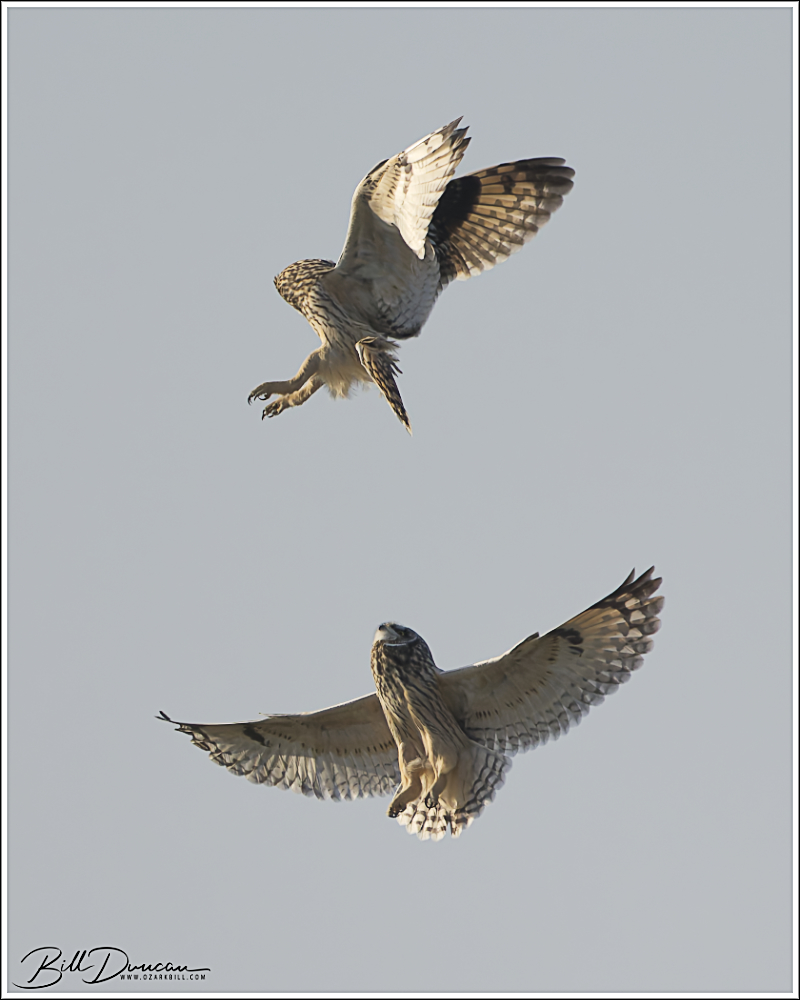

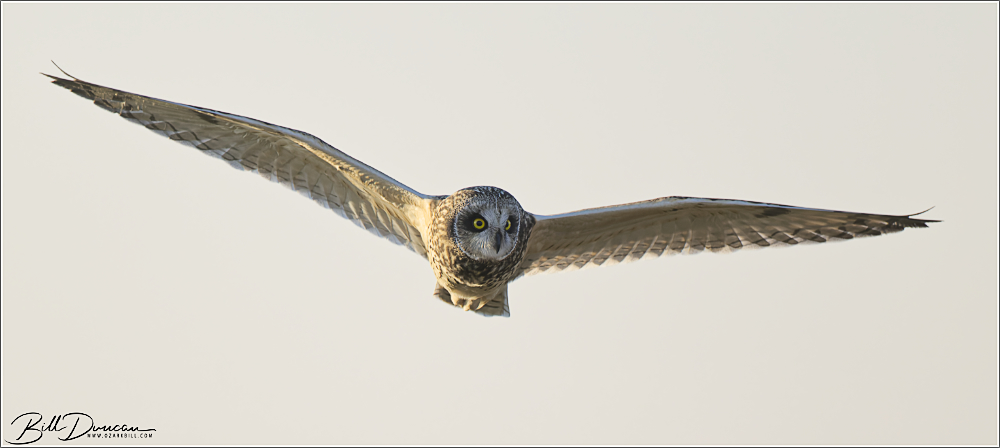

This post is dedicated to my friend and mentor, Godfrey Bourne. Godfrey researched Snail Kites for his Ph.D. work while at the University of Michigan. I remember listening to some of his stories and seeing photographs of this impressive bird of prey. Around 25 years later they were still high on my wish list to find and photograph. Last week, I just happened to have a work trip down to Orlando, Florida. I made sure I had time for a personal day or two and the Snail Kite was the primary species I sought out over all the impressive birds that can be found in the state.

After watching some videos from a well known bird photographer on YouTube, I got the impression that this species might be difficult to find – that these birds are only found in wetlands away from developed areas that take knowledge and special equipment to reach. With my experience last week, I am beginning to think that this photographer’s motive was in selling his high-priced workshops.

Don’t get me wrong, with a current population estimate of approximately 2,000 individuals in Florida, these are not common birds; in fact, they are listed as endangered in the United States. This is primarily due to overdevelopment of wetland habitat in the sunshine state along with mismanagement of these habitats that has led to the decline of apple snails – the Snail Kite’s only food source. Thankfully, this species has a large range across the neotropics, from Mexico and the Caribbean to Southern Brazil. The species as a whole is currently not threatened with extinction.

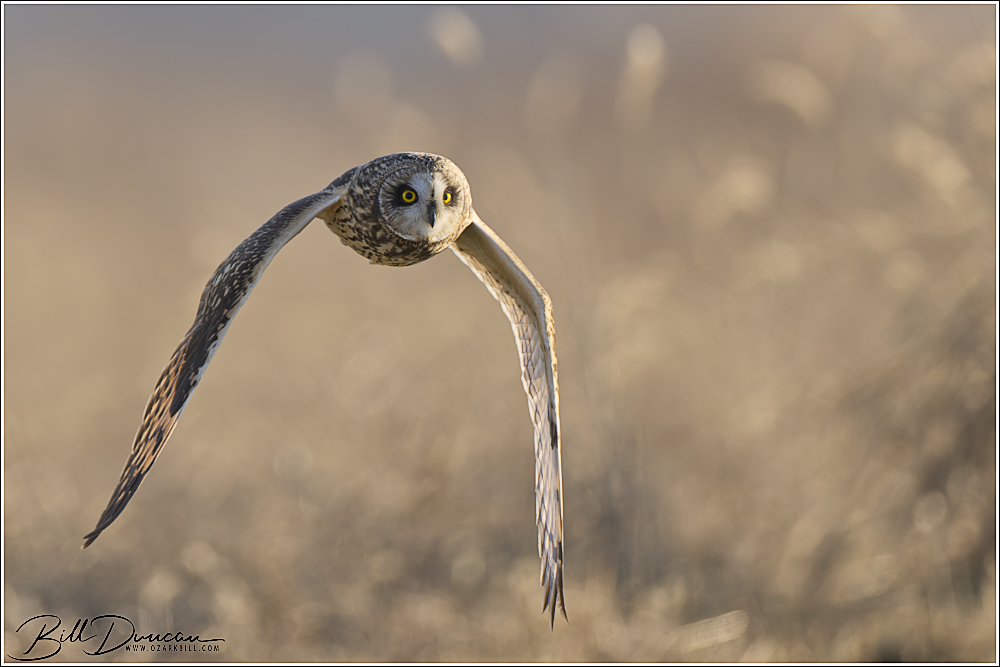

In two close by areas, only a 30 minute drive from Orlando, I was easily able to find four Snail Kites and watched them for hours in a lake/marsh area that was heavily used by recreating people. Seeing as this is an endangered species, my intention was to give them plenty of room, but I was shocked as I watched people pass by them within just 10 feet or so without the birds seeming to care. On a couple of occasions, I sat down under a shade tree with 50-100 feet between me and the bird and was astounded when they flew closer and closer to me during their foraging. I have always said that any bird photograph taken in Florida should have an asterisk attached due to these birds being so accustomed to people. After just a couple of days experiencing this myself, I still feel this way!

This species numbers in Florida are highly affected by drought conditions and have varied wildly in recent decades. Changing climate patterns are not helping the Snail Kite restoration attempts and I fear for what the next decades may bring. Hopefully they will be as easy for me to find during my next visit to Florida. Thank you for reading this far and I’ll leave you with a few more photos.

-OZB