Virginia snakeroot (Endodeca serpentaria) is an easily overlooked cousin of the much more familiar Dutchman’s pipevine (Aristolochia macrophylla). Belonging to the Aristolochiaceae (birthwort) family, both species host the pipevine swallowtail butterfly. The Aristolochiaceae family is composed primarily of tropical woody vining species. Virginia snakeroot is an exception in the family, being neither tropical, woody nor a vine. This species is a low and slow growing herbaceous perennial native to Missouri and is a really nice find.

Category: macro

Osmia taurus – Taurus Mason Bee

Casey and I found these mason bees in mid April this year at Hughes Mountain N.A. I had no clue what these were but was intrigued to “discover” a new-for-me bee so early in the season. Unfortunately, I was to find out it is yet another introduced species. Apparently these were first found in Maryland in the 1970’s and have spread west since then.

Hardworking for Hyperactive Hesperiidae

This season Casey and I have been focusing on trying to find some of the more rare and harder to find skipper butterflies in the family Hesperiidae. We’ve come up short a few times – there are several who seem to be on severe declines in our area and may be extirpated from previous well-known sites. Here are a few we had luck with finding and worked our tails of to get a few photos.

Atrytonopsis hianna (dusted skipper)

This striking skipper was found in the glades of Jefferson County, MO in May of 2023.

Problema byssus (byssus skipper)

Classified as vulnerable by the Xerces Society, the byssus skipper uses eastern gamma grass and big bluestem as its host and is threatened by the continued loss of prairie and grassland habitat throughout its range.

Euphyes dukesi (Duke’s skipper)

Uncommon throughout its fragmented range, the Duke’s skipper uses sedges in moist fields, marshes and forests for its host. This species is highly vulnerable to ongoing draining and development of these habitats. Casey and I refound this particular population in St. Charles County and we were happy to find a few in ditches alongside heavily trafficked roads.

Amblyscirtes hegon (pepper and salt skipper)

With a very large range, covering most of the eastern U.S., the pepper and salt skipper is nevertheless difficult to find and photograph.

From the Garden – Physocarpus opulifolius (Ninebark)

Peacock Brenthia (Brenthia pavonacella)

Here is another set from the bowels of Facebook that I wanted to make sure gets captured here. This is the diurnal metalmark moth (Choreutidae), Brenthia pavonacella (Hodges #2627). It is known as the peacock brenthia, due to its unusual mating display behaviors that can be seen here.

Schinia nr-jaguarina (French-grass Flower Moth)

These are some older photos that I posted on Facebook back in 2018 when I had the annoying habit of posting some interesting topics only on Facebook for some reason.

Only discovered in 2012, this species of flower moth (Schinia nr-jaguarina) has yet to be described and named. This was photographed at Desplaines State Fish and Wildlife Area near Joliet Illinois. This species seems to be an obligate feeder on Orbexilum onobrychis (scurf pea, french-grass, among others). To read more about this recent discovery, head over to this location: http://jimmccormac.blogspot.com/…/interesting-moth-new…

2023 Update

This past weekend, the WGNSS Entomology Group spent the better part of a day exploring the wonderful Horn’s Prairie Grove LWR, just north of Vandalia, IL, and discovered a population of Schinia nr-jaguarina (apparently, this species has still not been officially described and the specific name given here is just a placeholder).

One of us collected a specimen to rear so I might be able to get photographs of an adult soon.

Some Lovely Lycaenids

Tonight I’m just sharing some photos of a few lovely Lycaenid butterflies that I had the pleasure of photographing this season. The Lycaenidae family is the second largest family of butterflies, with about 6,000 species worldwide. The highlight was the bountiful season that the juniper hairstreak (Callophrys gryneus) had. Prior to this year, I had only seen one or two in a season, usually without my macro rig with me. In a few trips to the glades in Jefferson County this spring, Casey and I had at least two dozen individuals. They are not usually cooperative, but we worked pretty hard to get something.

First up is the afore mentioned C. gryneus.

Passionflower Flea Beetle (Disonycha discoidea)

Ever since seeing the photo of Disonycha discoidea in Arthur Evans’ “Beetles of Eastern North America,” I have been wanting to find and photograph this gorgeous Chrysomelid. I have looked for years for this species around St. Louis and southeastern Missouri, and even planted one of its host plants, Passiflora incarnata, in our yard hoping to possibly attract them.

Just a couple weeks ago, my friend, Pete, posted a bunch of picks from his botany trip to southern Illinois on Facebook. As I perused through his collection of fascinating plants he found, I stopped at a photo of several beetles that were on a grape vine. In this photo was a single D. discoidea. Getting a little upset, I messaged Pete to see if he could tell me exactly where he had found this. He was at Giant City State Park and because of smartphone technology, he forwarded me his geotagged photo and I had access to exactly where he had taken the picture.

However, I knew this was a big risk and I didn’t get my hopes up. First, Pete had taken his photo approximately a week before Sarah and I took the 2.5 hour drive south. In addition, the beetle he photographed was on a grapevine, not their typical host plant. Was this just an accidental occurrence of this beetle or could they use grapes as an alternative host? Nothing in the literature suggested that this occurred with this species; apparently, it is monophagous and only uses members of the Passiflora to feed.

We decided it was worth the drive. Giant City State Park is a high quality area and I knew that if we struck out we wouldn’t have to try hard to find something else of interest. We found Pete’s spot of original find pretty easily and started searching. After a couple hours of looking as hard as we could among the grape and poison ivy we decided we weren’t going to find the species there. Utilizing smartphone technology again, I thought it might be a good idea to look for Passiflora plants that had been documented in iNaturalist within the park. My phone signal was pretty poor, so we drove to one of the highest points we could find and I found a single spot that had these plants documented.

These plants were found in a poor scrub prairie habitat along with blackberry and even more poison ivy. We started looking, finding and searching between 50 and 100 of these short plants. We looked very closely and I had a chance to try my DIY collapsible beat sheets that I made over the winter. No luck. I couldn’t believe it. I really thought we had a good chance. We knew the species had been found in the park and here we were within a sizeable population of the host plants. You’ve seen the photos already, so obviously we found our target. And, of course, insect finder extraordinaire, Sarah, was the one to find the beetle on a ragged, half-eaten P. incarnata plant. I immediately got to work photographing from a safe distance. One of the reasons they call them flea beetles is that they will jump great distances upon being disturbed. Ultimately, we found four individuals all on the same plant. Thankfully, this species is quite large for a flea beetle and I didn’t need to get too close that higher magnifications would require.

So what’s up with that coloration?

This species exhibits aposematism, also known as warning coloration. This is the same reason that unpalatable or downright toxic species like monarchs and milkweed bugs along with stinging predators like yellowjackets or velvet ants show warning colorations. Disonycha discoidea picks up cyanogenic glycosides from its Passiflora host plant, making it distasteful or toxic to would-be predators. By evolving this aposematism, the insects can advertise this and avoid the predators that would be on the lookout for an easy meal. In the tropics, a group of butterflies known as the heliconiines also acquire these toxic compounds from the larval feeding on Passiflora.

It was great to finally find this target species. The larvae of this species is also quite photogenic. If I find the time to make a return visit this summer, I would love to find a few of them as well.

Thanks for stopping by!

OZB

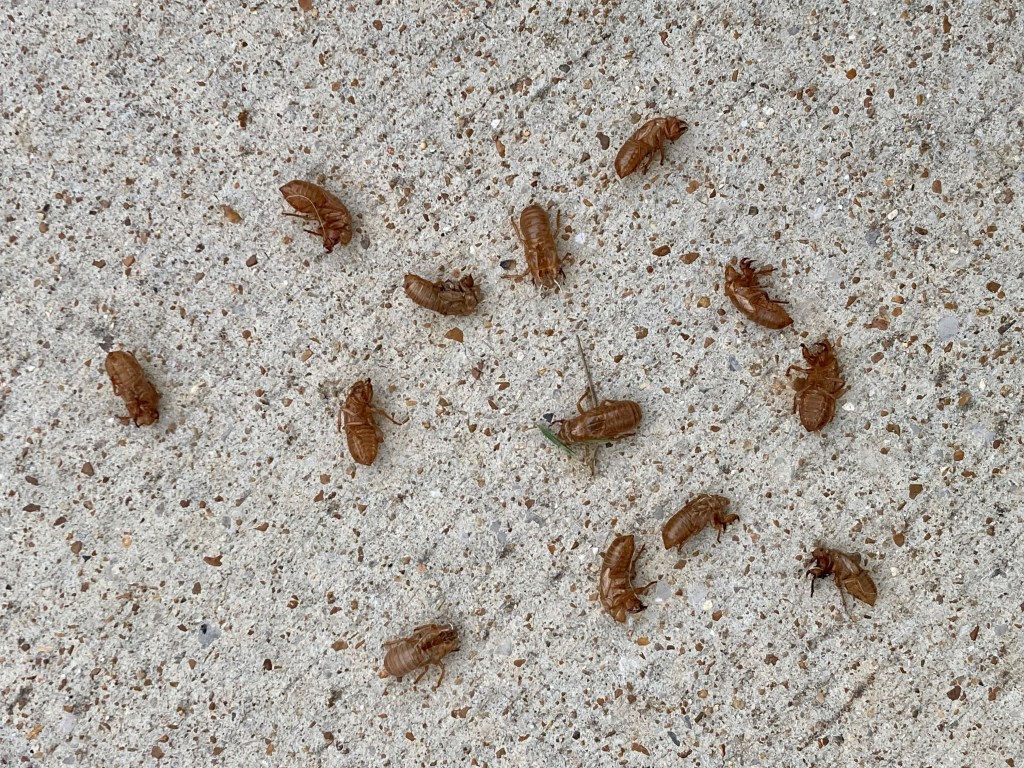

An Early Rise from Brood XIX?

During my morning walk in our Chesterfield suburban neighborhood this morning, I found quite a fascinating thing! I ran across several groups of periodical cicadas (Magicicada spp.) that had emerged during the night. I estimate that I found approximately 250 of these large hemipterans without leaving the sidewalk!

I am not quite certain about what exactly is going on here. Our next big emergence of these insects is supposed to occur next season in 2024 – the so-called “Brood XIX.” Brood XIX is composed of four species of periodical cicada (Magicicada tredecim, M. tredecassini, M. tredecula, and M. neotredecim) that all follow the 13 year emergence pattern.

Why are we seeing these emerge this year? A couple of possible explanations could account for this. These could be “stragglers,” the term used to describe individuals that emerge in years before or after the bulk of the particular brood. This makes evolutionary sense; if the entire brood emerged all on the same year (emergence of the entire brood within a given location occurs within a couple of weeks) and they are struck with a weather or some other disaster, then this would be a very bad day for the brood. With some individuals emerging a year or two before or after the primary year, then this would obviously be beneficial in hedging their bets.

Another possible explanation is that this could represent a sub-population of Brood XIX that is on a slightly different schedule and may routinely emerge early. This could be due to differences in climate patterns between this one and what the rest of the brood experiences. Brood XIX covers a large area of the southeastern U.S.

Or, could this be the result of some differentiation between emergence patterns between the four species that constitutes Brood XIX? I don’t know but I would love to hear any thoughts from those of you who are more educated and experienced in these things than I am. I will be keeping my ears open during the next several weeks with hope of hearing this rare song.

Thanks for stopping by!

Ozark Bill

Insect’s of Horn’s Prairie Grove LWR

The WGNSS Entomology and Nature Photography Groups had a splendid treat in July of 2022 when we jointly visited Horn’s Prairie Grove Land Water Reserve (LWR) near Ramsey IL. This 40 acre patch represents part of the less than 1% of the remaining southern till plain prairie ecosystem that was nearly wiped from the planet due to land conversion for farming. Even better, about 30 acres are original “virgin” prairie, (the largest intact remnant prairie in IL) meaning these spots were never touched by the plow. Even better still, at this location there lies five different types of prairie habitat: seep/wetland, dry hillside, mesic, black soil and savanna.

The story of this land is interesting. The current owners, Keith and Patty Horn, purchased the land in 2001 as “junk land” from an old farmer who’s family had owned since the 1870s. They liked the fact that the majority of the land was in a “wild” state. The untouched 30 acres had been used as a wild hay field, being cut almost yearly. They had noticed some nice wildflowers in bloom but did not realize what they had until a few years into a wildlife habitat improvement plan that included periodic burning. Every year they noticed more and more species in bloom. They have sought help in identifying the plant species here and the current list is now at 619 species, including six native orchid species! Bravo to the Horns for identifying what they had and taking the steps to see their land improved. This remnant prairie could have been destroyed in the blink of an eye if it had fallen into the wrong hands.

Although most of us were simply thrilled to be in such high quality habitat, the primary purpose of the trip was to check out the arthropod life. Unfortunately, in late July, we were there on a truly miserable day of weather. The heat and humidity created a heat index that was well above the safety zone. This meant not many of us had the nerve to do a great deal of walking and searching, especially much after lunch time.