During this past weekend the WGNSS Nature Photography group met up with our friend Dr. Rick Essner from SIUE to see and photograph one of our favorite subjects, the Illinois chorus frog (Pseudacris illinoensis) . I first wrote about these wonderful little guys a couple of years ago when Rick helped a few of us see them for the first time.

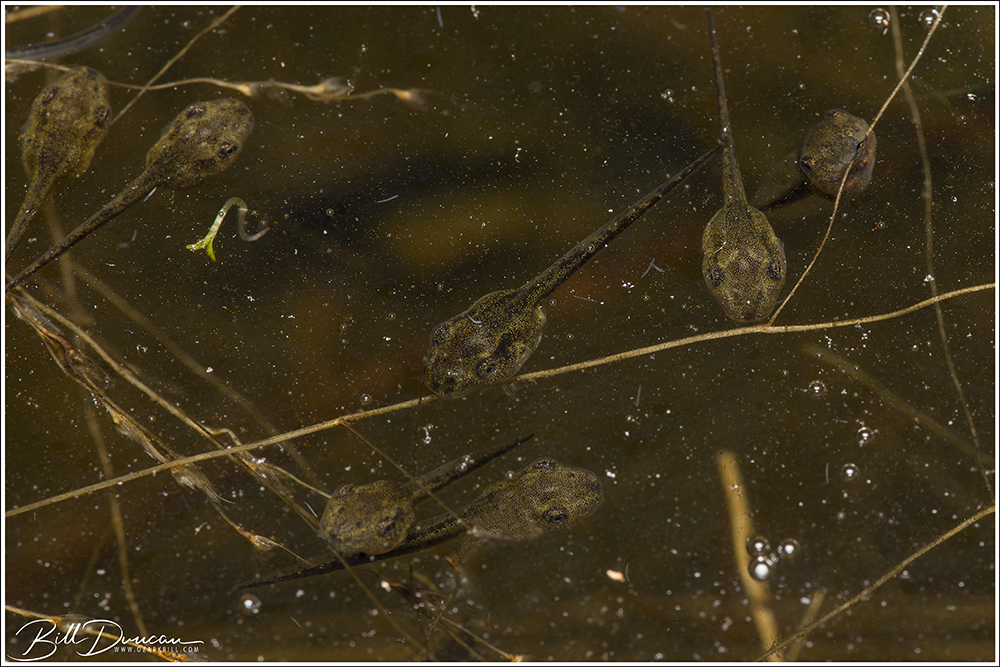

This year’s visit was perfectly timed for my primary photography goal, which was to photograph this species during amplexus. Our first stop was at a sand-prairie habitat where the frogs use small plastic basins that are set into the ground in order to keep the standing water these frogs need to deposit eggs and the resulting tadpoles need for their development. In addition to these artificial basins, the land mangers at this and a nearby sand prairie tract have recently installed larger ponds with liners to retain water long enough to see the frogs through their development cycle without the need to worry about egg-predating fish. These ponds were only installed this winter, however, and cover-providing vegetation and structures in the water are not yet established. We only found a couple of frogs at these locations but hopefully these new ponds will support a strong breeding population in years to come.

Getting photographs was not the primary reason Rick and his students were out on this fantastic evening. The biologists at SIUE are using mark-recapture techniques to study population demography and spatial activity, as well as the frog’s feeding behavior, locomotor behavior, and diet. It was fascinating to watch the students insert the smallest available PIT (Passive Integrated Transponders) tags in order to identify individual frogs in order to monitor their growth, movement and other characteristics over time.

After finding a few frogs in the sand prairie, we followed Rick and his students to other potential locations that might contain breeding frogs. We found what we were looking for in a location that was somewhat unfortunate but definitely contained what the frogs were looking for. At a drainage ditch between a small blacktop road and an agricultural field we found a group that I estimated to be between 25 and 50 Illinois chorus frogs along with quite a few American toads (Anaxyrus americanus). Here we easily photographed pairs in amplexus and struggled to photograph calling male Illinois chorus frogs.

In order to photograph the frogs with inflated vocal sacs during their vocalizations, we first needed to find the solo males that were vocalizing. This was the first challenge. The unpaired males seemed to have a high preference for vocalizing under the cover of the short vegetation along the banks of the ditch. This made finding them quite a difficulty. Additionally, as anyone who might have the experience of attempting to find vocalizing frogs will know, they exhibit what could be called a ventriloquist effect. As the observer hones into the location where the frog must be calling from, it is simply impossible to find. This effect is hypothesized to be an adaptation to predation avoidance. A stationary frog, vocalizing at incredible decibels, could be seen as ringing the dinner bell for predators with the ability to use auditory cues to track their prey. This may help with predator avoidance, but then how does the female find her chosen mate with the sweetest voice?

Finding the vocalizing males was just half the battle. In order to photograph these guys at night, we must shine a light in order to focus on them. More times than not, as soon as I trained my focusing light on to one of them, they would quit calling. It would then take quite a while for them to get started again after sitting still with the lights out. It took me quite a few attempts to get the few successful images I was fortunate to get.

When male frogs are in a perfect situation such as this, they are eager for ANY opportunity. If it moves and in any way matches their search pattern – namely, any other frog, they are known to grab and hold on, whether that be a conspecific female or male, or sometimes something even more, shall we say, less evolutionarily appropriate…

That’s all I have to share from this wonderful evening. I’m happy to see that researchers at SIUE are studying this threatened species and that the land managers are making strong attempts at improving breeding habitats for this wonderful species.

Thanks for the visit!