This post is a modified article that was originally published in the Webster Groves Nature Study Society’s journal, Nature Notes (February, 2020, Vol. 92, No. 2).

The alarm on the phone sounds off at 4:00 am. You have a quick, light breakfast but no coffee. Making moves required during the act of recycling that coffee would be detrimental to your goals this morning. You’ve packed the car the night before, so you simply need to wash your face and throw on the required number of layers it will take to stay warm enough during your several hours sit. This requires some critical thought as morning temperatures during the rut can often be in the teens or twenties.

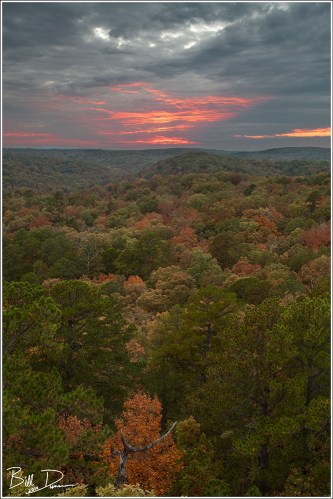

You arrive at the site by 5:30 am and are under cover at your pre-scouted location by 6:15 am — first light. Sunrise and the golden-hour will come in about 30 minutes. You picked this location due to heavy deer traffic signified by sign such as tracks and scat, scrapes and rubs. You put your back to the rising sun to take advantage of the beautiful golden-hour light that will be splashed across the scene. You also considered the potential background for your photos. You made sure there is plenty of space between your subjects and a natural, potentially autumn-colored background to get that creamy, out of focus quality that helps your magnificent subject stand out. Remember, the key to improving your nature photography is to make the photo, not simply take the photo. Previsualization and planning are often critical!

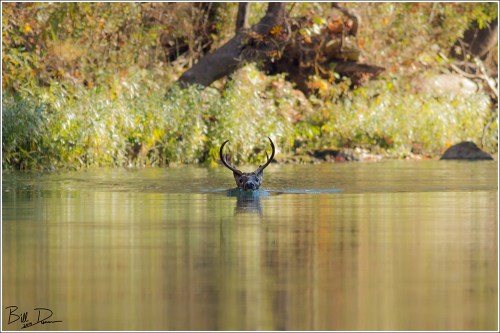

Arriving prior to first light brings the best potential for being unnoticed in your blind. However, deer are often just as active at night and sometimes you may find your spot is already occupied by your subjects! Don’t worry too much; you may spook those deer out of the area, but there are plenty of others who will likely visit these hangouts before the morning is over. Where you choose to photograph will be important in this respect. Take advantage of photographing in areas that are closed to hunting, like parks and sanctuaries. Here the deer are very accustomed to people and our scents, showing little fear. Often, during the rut, younger bucks may be curious and will move closer to you. You will typically need to work harder to get closer to the wearier does and old, veteran bucks who have been around the block a few times. In non-hunting areas, you can often get close enough to your subjects to make meaningful photographs by simply having an early-morning walk around with a longer telephoto lens (e.g. 300-600 mm focal length).

Like clockwork, at 6:30 am every morning, large flocks of blackbirds move overhead from the west, chasing the rising sun in search of feeding grounds. Photographing the rut is very similar to hunting. Deer hunters in our area typically use tree stands. This higher elevation provides advantages in being able to see greater distances, being out of direct eye-line of the deer and aids in dispersing your scent, which is frequently a give away of the pursuer. When hunting with a camera and lens, you need to stay on level ground and shoot the deer at eye level or lower.

A method Miguel Acosta and I like to use is hiding in a blind (we like the portability of ‘throw-blinds’) along well-established deer trail or nearby communal rub or scrape areas. This will require using camouflage, blinds or similar methods to break up the human form. In the types of areas described above, you need not worry too much about your scent. Deer have very strong sense of smell and in the middle of an unpopulated forest, your odors can very easily give you away. But, in areas like parks where people and deer are often found in close proximity, your own scent is less likely to alarm the deer and thereby allow you to get much closer.

Around mid-morning a Red-shouldered Hawk, perched above our location, vocalizes and a mixed-species flock of songbirds moves into our copse of trees. Since we have our large lenses, we try our hands at photographing Chickadees and Titmouse. Although scent and wind direction may not play an important role in this setting, being quiet is important for getting those close and intimate shots. I recommend doing everything you can to keep your noise to a minimum. Try and chose gear without Velcro or other noisy fasteners. Keep your voices to a minimum and try not to move frequently. If available on your camera, choose the “silent shutter” setting. Many dSLR cameras have this setting that lowers the volume of the mirror flapping. Consequently, this will lower the frame rate of the camera, but this is preferable to spooking your subjects before you get your shots. New mirrorless cameras lack the mirror box of their older brethren and can shoot very quietly at high frame rates.

Later in the morning I awake from a nap to the sound of Wild Turkeys vocalizing. I quickly realize that a small flock have wandered near our location and Miguel is offering them some verbal enticement to come a little closer to our shooting lane. It didn’t work, but the fact they were within ten yards of our location offers further proof that our blinds and technique work to get us closer to wild animals. Until recently, I had never given our North American game species much thought as a subject of natural history study. I’m sure that not growing up as a hunter or outdoorsman has had an influence on this. Over the past couple of years, I have fallen hook, line and sinker into learning everything I can about white-tailed deer and finding ways to best capture them with the camera. Miguel and I have much to learn and we are eager in making more photographs, capturing their different behaviors and at different times of the year.

For recommended reading about the rut and other aspects of the lives of white-tailed deer, I recommend reading any books you can find by authors Leonard Lee Rue III and Mark Raycroft.