It’s February already and I’m still trying to wrap up photos from last year. Here are some photos of odonates from 2023.

Author: Ceibatree

Falcate Orangetip (Anthocharis midea)

These are not the photos I envisioned getting when going after the falcate orangetip (Anthocharis midea). Casey and I must have spent more than a couple of hours running around Hugh’s Mountain Natural Area, waiting for one of these gorgeous males to land at a flower to nectar. Unfortunately, this rarely happened, and when they did finally set they were up again within seconds.

These guys were definitely not interested in feeding while we were there, instead they incessantly roamed the glades and woodland edges hunting for females. This is where I finally got a little bit of luck by finding a stationary female. She had drawn the attention of several males who were fighting for a chance to breed.

Members of the Pieridae family, the falcate orangetip’s host are members of the mustard family (Brassicaceae). The caterpillars feed mostly at night on the flower tissues of these plants.

Nymphalids of 2023

I was happy to final start working on getting some butterfly and skipper photos in 2023. I joined the local North American Butterfly Association and really enjoyed getting out on a few of their counts. I’m still learning the diurnal moths (butterflies) and have a ways to go before I can call myself competent. Here are a few photos from the Nymphalidae family to share from 2023.

This gemmed satyr was an unexpected find while visiting St. Francois State Park in September. Not long ago this species was restricted to extreme southern Missouri. They now seem to be continuing a northern expansion in their range. Quite a few butterflies have eyespots that are found on different locations of their wings, presumably to make them look like much larger organisms as well as to persuade would-be predators to attack something beside the vulnerable true heads. I have recently read that some have hypothesized the spot on this species wings developed to mimic certain jumping spiders. In my photo I think this looks to be highly plausible – with the two primary eyes centered around a grey backdrop that looks very much like a jumping spider to me.

Once believed to be a pure example of Batesian mimicry in a complex with the monarch and queen butterflies, some evidence now suggests that the viceroy may be distasteful to predators, providing evidence that this is instead should be considered a case of Müllerian mimicry. This is turning out to be quite the complex case to understand, with some reports suggesting that the host plant that a particular individual viceroy was raised on determines whether or not it is distasteful. Other work has suggested that gene complexes that may differ between populations of viceroys determines distastefulness. More work is needed to determine what exactly is going on here. This photo was taken on a NABA walk ate Marais Temps Clair C.A. in September.

Photographed at Marais Temps Clair C.A. in early October, the red admiral is a lover of nettles, feeding solely on members of the Urticaceae family.

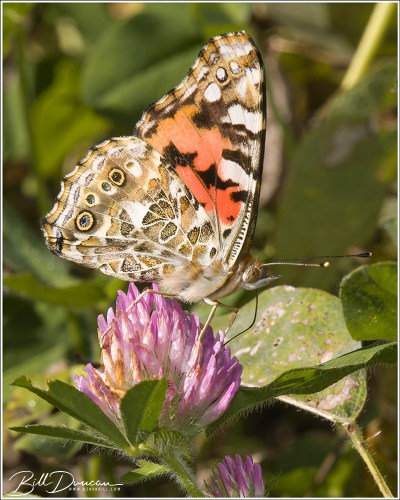

Famous for its migration, the painted lady hosts on numerous species of Asteraceae.

Being strictly found in the new-world, the American lady can be distinguished from the painted lady by the number of spots on the ventral sides of the hindwings. As seen in the photo above, the American lady has two large eyespots whereas its cousin, the painted lady, has four. Photographed at Horn’s Prairie Grove LWR in July.

WGNSS Went to the Zoo!

The WGNSS Nature Photography Group headed to the St. Louis Zoo during a frigid winter spell this past weekend. Light could have been better and we struck out on a few things we were targeting, but I am pleased with a few images I was able to make. Everyone was well bundled for the conditions and I think had a nice time.

The St. Louis Zoo also contains a number of species native to Missouri, most of which are rescued animals that have poor chances of survival in the wild. Some, like the eastern grey squirrel and eastern cottontail, along with some waterfowl and wading birds are wild species that stick to the zoo grounds looking for easy meals.

Short-eared Owls at RMBS – 2023/24

Despite being a pretty disappointing season for winter birds so far, due to not being much of a winter season, one saving grace has been the unprecedented appearance of a number of Short-eared Owls that have set up shop in the grasslands at Riverlands Migratory Bird Sanctuary near the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. It seems as though every birder and photographer in the bi-state area has heard about this and show up regularly to view the spectacle.

Finding the opportunity to be there in good light with the birds cooperative has been a challenge for me over the past month or so they have been here. But, I did have some luck under less than optimal skies. Despite poor lighting and the birds being a little further away than I would like, I was able to manage a few images I can live with. I’m hoping to have a few more opportunities before the season is over.

Caterpillars of 2023 – The Rest

Today I’m finishing up with the remaining cats of late summer and autumn hunting trips of 2023 from an assortment of families.

Walnut Sphinx Moth (Amorpha juglandis) Sphingidae, Hodges#7287

These are among my favorites. Not only are they quite handsome when viewed up close, but they are one of the few caterpillars with a voice! Be prepared if you handle or otherwise disturb them; they will let out a surprising squeak when they feel threatened.

Curve-lined Angle (Diagrammia continuata) Geometridae, Hodges#6362

Casey and I observed that the juniper hairstreaks (Callophrys gryneus) had a bumper year this year while hiking in glades early in the season. We thought this might be the year to finally find the fantastic larvae of this species. We spent several hours beat-sheeting the red cedars in these areas in late summer and early fall. No luck in finding that species, but we did find another inconspicuous cat that uses this plant as its host. You can probably see that, like the hairstreak, the caterpillars of this moth species would be next to impossible to find without the use of a beat-sheet.

Undescribed Flower Moth (Schinia nr-jaguarina) Noctuidae, Hodges#11132.01

I shared photos of this yet to be described species before. These are photos of the cats we found at a new location, Horn’s Prairie Grove LWR, in central Illinois.

Red-lined Panopoda (Panopoda rufimargo) Erebidae, Hodges#8587

An interesting cat we found while beet-sheeting a hickory thicket on a friend’s property in St. Francois County.

Pipevine Swallowtail (Battus philenor) Papilionoidea

Conspicuous and distasteful due to the absorbed secondary chemicals of their pipevine host, it seems like we always find these guys in low-light situations, making the use of supplemental light a necessity.

Giant Swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes) Papilionoidea

My favorite swallowtail species. It was a real treat finding this final instar cat back in September.

Heart and Soul Nebulae @ 260mm

The Heart and Soul Nebulae

Located near the constellation Cassiopeia in the Perseus arm of the Milky Way lies a pair of well known nebulae, birthing stars and wonders. The well-named Heart Nebula (Sh2-190, IC 1805) and the less well-named Soul Nebula (Sh2-199, IC 1848) lie approximately 7,500 and 6,500 light years away respectively. Both are made up primarily of hydrogen gas and this condensing gas is the birth process of stars. Near the center of the Heart Nebula is an open star cluster of such newly formed stars known as Melotte 15. These stars have taken up much of the hydrogen and other gases from the nebula center and these young and bright stars light up the surrounding hydrogen gas, causing it to emit light in the red visible colors. Also of note in this image is the “fish head nebula” near the bottom of the heart, catalogued as IC 1795.

This image captures a relatively huge portion of sky and covers an area more than 600 light years across. Click here to see a fully annotated version of this image.

I find that the Soul Nebula, although a poetic match for its bigger neighbor, is poorly named. It may be difficult to see in my rendition, but in images with more defining details, I think this one should have been named the “chubby baby nebulae.”

Collecting the data

October was another cloudy one around the new-moon period. Luckily we had what looked to be a great night on the new moon. As usual, the forecast let us down a bit. Due to issues Miguel had in one of his previous outings with a Conservation Agent at Whetstone C.A., we decided to go back to our spot at Danville C.A.

Conditions

For a November outing the temperatures could have been much worse. We bottomed out at 42° F and winds never rose more than 5 mph. The forecasting apps all suggested a mostly clear night. Unfortunately, we were plagued with narrow bands of cirrus clouds that seemed to park themselves in between us and our target. These were barely perceptible to the naked eye, but they affected at least 25% of my subs over the course of the night.

Equipment

Astro-modified Canon 7D mkii camera, Askar ACL200 200mm f/4 lens (260mm focal length equivalent), Fornax LighTrack II tracking mount without guiding on a William Optics Vixen Wedge Mount. QHYCCD Polemaster. Gitzo CF tripod, Canon shutter release cable, laser pointer to help find Polaris and sky targets, lens warmer to prevent dew and frost on lens, dummy battery to power camera, lithium battery generator to provide power to camera, dew heater and laptop computer.

Imaging Details

Lights taken (ISO 2000, f/4, 120 second exposure): 153

Lights after cull due to tracker error, wind, bumps, clouds, etc.: 131

Used best 90% of remaining frames for stack for a total of 118 subs used for integration (3h 56m)

Calibration frames: none

Processing

RAW files converted to TIF in Canon DPP, stacked in Astro Pixel Processor, GraXpert for gradient removal, Starnet++ for separating nebulas from stars, Photoshop CS6 for stretching and other cosmetic adjustments.

Problems and learnings

I know this section has just turned into a bitch session and this night was a bit on the rough side as well. First, I was disappointed in myself for the time it took to properly compose the target. Finding the object wasn’t too difficult, but because of the faintness of the targets, I just couldn’t get my mind together to make this tight framing (this image is only slightly cropped). After wasting nearly two hours of dark skies on getting the final composition and then having to do a second polar alignment (I think I must have nudged the tripod while making composition adjustments), I was finally taking images.

Next the periods of clouds. I continued to let the camera go even though I knew I would be tossing some frames. I culled about 20 frames due primarily to clouds but I left another 20 or so in the stack that I thought wouldn’t hamper the final result.

Typically, I can arrange the rig and counterbalance bar so that I do not require a meridian flip. I guess in my frustrations in finding and composing, I neglected to think about this. Yep, somewhere around midnight, I realized the camera was going to be running into the tracking unit if I didn’t perform this flip. Of course, doing this manually, meant I had to go through the process of finding and composing the target again! This time didn’t take me nearly as long and I was back to shooting in about 40 minutes or so.

All of the above explains why I was only able to collect about half of the data that I should have been able to on a night like this. The clouds got bad enough towards the end of the night that I shut down with more than an hour of usable night left.

Conclusion

With the challenges on this night, I guess I have to be satisfied that I have something to share. This is another popular target that most astrophotographers get to pretty early. November is by far the best month for this target as it is viewable from the beginning to the end of night. There are a few other compositions to consider here, like shooting each nebula separately, or even focusing in on the heart of the heart – Melotte 15. So, I definitely have reason to revisit this section of the night sky someday.

Caterpillars of 2023 – The Noctuidae

Here are a few of the members of the Noctuidae family of moth caterpillars we found in 2023. Commonly know as “owlet moths,” this is a very diverse clade that is still continuing to be revised and divided. Until recently, this was the largest lepidopteran family. A number of economically important members are found in this family, such as armyworm and cutworm species.

American Dagger Moth (Acronicta americana) Noctuidae, Hodges#9200

Rarely a day on the hunt goes by without finding one or more of these little beauties. This guy was not perturbed at all by us stopping to watch. It continued to chow on the leaf as I photographed it.

Two-spotted Oak Punkie (Meganola phylla) Noctuidae, Hodges#8983.1

Found on Quercus alba (white oak).

Eclipsed Oak Dagger (Acronicta increta) Noctuidae, Hodges#9249

Not that I keep great records but I am pretty certain that this one is by far the most abundant caterpillar we come across while looking on oaks. I probably find five of these to one of other species on oaks. There are a few similar species. The second one may be a different species of Acronicta.

Noctuidae (Acronicta sp.)

This is what I get for not taking photos of some of these from multiple angles. Not even the experts on iNaturalist could get this guy to species using this one image. It was a gorgeous and large caterpillar.

Gold Moth (Basilodes pepita) Noctuidae, Hodges#9781

Finally – I am sharing a cat that does not feed on woody plants. Also, a rare case of a moth that is gorgeous in both adult and larval forms. Unfortunately, this was a pretty early instar and does not show the bright and contrasting colors of older caterpillars. The gold moth feeds exclusively on Verbina species (wingstems, crownbeards).

Have a good one!

-OZB

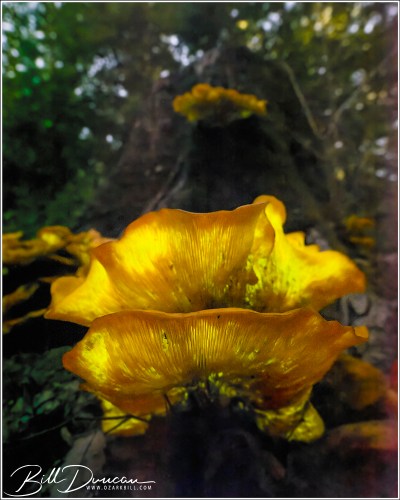

The Perfect Halloween Fungi – Eastern Jack-o’-Lantern Mushroom

I have long waited to find and photograph the eastern jack-o’-lantern mushroom (Omphalotus illudens). With as dry as this past summer and autumn have been, this has been a terrible year for finding mushrooms of most types. So, I was quite surprised when Pete Kozich sent me a photo showing a large bunch O. illudens growing around a dead hardwood stump at a nearby location in St. Charles County. We arrived shortly after the beginning of astronomical night in order to be able to capture the bioluminescent glow that this species is well known for.

The pale yellow-green bioluminescence, colloquially known as “fox fire,” is only found in the lamellae (gills) of fresh mushrooms. We were somewhat disheartened when we arrived, finding the majority of the group to be well past their prime. Thankfully, there were still a few caps that were fresh enough that we could perceive the glow with our dark-adapted eyes and with the camera.

Bioluminescence in the Fungi kingdom is quite rare. Of the approximately 100,000 described fungi, only 71 species have been reported expressing this trait, all within the Order Agaricales, or gilled mushrooms (Stevani et al., 2013). The cause of the bioluminescence in fungi is due to the activity of the enzyme luciferase working on its substrate – luciferin. The selective advantages of concentrating these compounds around the gills of the mushrooms are not exactly known, but it has been hypothesized that light emitted from bioluminescent fungi attract nocturnal arthropods that may aid in the wider dispersal of spores (Oliveira et al., 2015). Pete and I noticed a number of insects, namely craneflies (Tipuloidea), which were hanging around the gills of the fresh mushroom caps. Whether the bioluminescence or the rotting mushrooms surrounding these caps were the primary bait drawing these insects, I can only speculate.

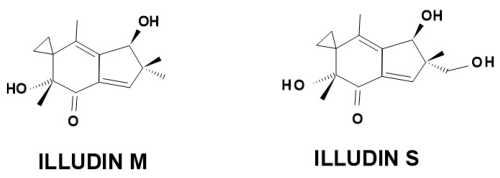

Although these mushrooms slightly resemble and smell as wonderful as a basketful of sweet chanterelles, the jack-o’-lanterns are not too be eaten! This species produces the sesquiterpenes – illudin S and illudin M, chemical compounds formed as secondary metabolites in the fungus . The illudins are quite toxic and will make one extremely sick when eaten. There is an upside found here, however. Illudins are known to be antineoplastic and are now being used in the development of anti-cancer drugs.

Photographing O. illudens can be a challenge. These are best photographed when fresh caps with exposed lamellae are present. A night around the new moon would be most optimal. The two photos shown here, depicting the bioluminescence, were taken with the following camera settings: ISO 3200, f/4, and 5-minute exposures. In retrospect, I probably exposed these for too long. The bioluminescent glow would have been better emphasized with a bit darker of an exposure. These might look as though they were taken with some sunlight or artificial light source, but I can assure you it was very dark with only the light from a near-full moon.

Another thing I wish I would have thought of doing is to collect a cap or two and brought them home to photograph in a perfectly dark room. In doing this, the only light available would be that from the glowing mushroom. Ah well, we now know of a good stump that houses this fungus. With luck, we can try again next season a bit earlier and try this again.

Happy Halloween!

REFERENCES

Oliveira A.G., C.V. Stevani, H.E. Waldenmaier, V. Viviani, J.M. Emerson, J.J. Loros, J.C. Dunlap. Circadian control sheds light on fungal bioluminescence. Curr Biol. 2015 Mar 30;25(7):964-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.021. Epub 2015 Mar 19.

Stevani, C.V., A.G. Oliveira, A. G., Mendes, L. F., Ventura, F. F., Waldenmaier, H. E., Carvalho, R. P., & Pereira, T. A. (2013). Current status of research on fungal bioluminescence: biochemistry and prospects for ecotoxicological application. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 89(6), 1318-1326.

Caterpillars of 2023 – The Notodontidae

Today I am featuring the more interesting larvae we found of the Notodontidae Family, commonly known as the prominent moths. This is a widely distributed and diverse family with close to 4,000 species described worldwide. Hosts for this family are mostly woody plants and we often find these feeding on oaks and hickories.

Variable Oakleaf Caterpillar (Lochmaeus manteo) Notodontidae, Hodges#7998

Finding a lot more than I decided to photograph, this aptly-named species feeds primarily on oaks (Quercus sp.) and is highly variable in coloration and pattern. This is a species you may get tired of finding when focusing on oaks during your searches.

Mottled Prominent (Macrurocampa marthesia) Notodontidae, Hodges#7975

We found a few of these guys this year and I find these to be very handsome little cats.

Heterocampa pulverea, Notodontidae, Hodges#7990.1

Until recently, this was a pretty large genus, containing close to 50 species. A couple of years ago, armed with molecular data, this genus was split and now contains 18 species. This one was found on a WGNSS group outing at Pickle Spring Conservation Area in early September.

Orange-banded Prominent (Litodonta hydromeli) Notodontidae, Hodges#7968

We found this guy on another WGNSS outing while looking for the bumelia borer beetle (Plinthocoelium suaveolens). We did not find our target that day but I was thrilled to find this cat that previously I did not know existed. This is another specialist that only feeds on the gum bumelia (Sideroxylon lanuginosum).

Saddled Prominent (Cecrita guttivitta) Notodontidae, Hodges#7994

This is a very common species that feeds on oaks and until recently belonged in the genus Heterocampa.

White-streaked Prominent (Ianassa lignicolor) Notodontidae, Hodges#8017

Also known as the lace-capped caterpillar, this is one of many caterpillars in this family that hide in plain sight. You will almost always find these sitting on the section of leaf they have previously eaten, using their coloration and patterns to look like a diseased or senescent portion of the leaf. These can be quite tricky to find until you get the right search engine installed in your brain.

Red-washed Prominent (Oedemasia_semirufescens) Notodontidae, Hodges#8012

Although considered fairly common, this was the first year I was finally able to find one of these outstanding cats. This species is quite polyphagous, feeding on almost any native woody plants. One of the two we found this year was feeding on pawpaw (Asimina triloba).

Datana Caterpillars (Datana sp.) Notodontidae

Most notodontids are solitary. But certain groups, like these Datana are gregarious and can be found in large groups even in later instars.

Symmerista Prominents (Symmerista sp.) Notodontidae

Another gregarious taxa, the Symmerista are notoriously difficult to identify to species in both larval and adult phases.

White-dotted Prominent (Nadata gibbosa) Notodontidae, Hodges#7915

Perhaps the most common caterpillar we find on our hunting trips, the white-dotted prominent can be found in large numbers on oaks. We find these so often that I rarely even tell the others in the group when I find them. But here we find a common species in a not so common situation. We came across this one on its way to find its pupation spot that would likely be in the ground or leaf litter. You can tell this was the case by the reddish or maroon coloration. Many caterpillars will change to this type of coloration immediately before they begin the pre-pupal stage. Unfortunately for the caterpillar, some southern yellowjackets (Vespula squamosa) found it as well. We watched the drama unfold as the wasps continued to sting and bite at the poor creature that will not likely make it to adulthood.

Thanks for stopping by!

-OZB