"What a thousand acres of Silphiums looked like when they tickled the bellies of the buffalo is a question never again to be answered, and perhaps not even asked." -Aldo Leopold

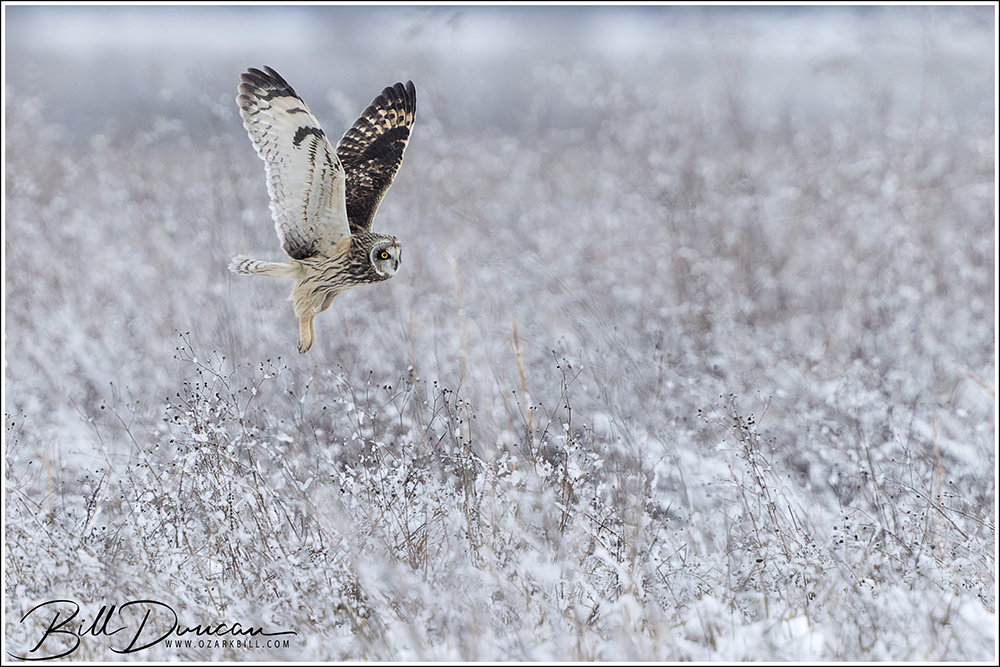

A few from a couple snow days this past January. Some of the first outings with the Canon R5. On one day, light levels were quite low and birds were at a great distance. Tried shooting with and without teleconverter to get more light. Difficult circumstances.

Ozark Bill

It’s been quite some time since I’ve shared a blog post. This has primarily been due to being in a residence move that is seemingly never going to end. But, I have been finding time here and there to make new images and even get some post-processing done. I have switched themes in this blog, picking a theme that should allow me to create a “portfolio” page to showcase my stronger photos. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to figure out how to do this in WordPress. So I have not gotten far in this endeavor.

My goal is to post more frequently, just to share photos. There may not be a lot of accompanying text, but will depend on the subjects, my amount of free-time and my mood.

The images in this post were taken back in April of 2019 during a WGNSS Nature Photo Group outing to Dunn Ranch Prairie. This visit was close to the end of the lekking period and was the latest date that the MDC was keeping the blind open. This was different than our previous visit when we visited in the earlier part of the season and had pros and cons associated.

Visiting the lek later in the season created better chances for better light (clear skies) and warmer weather. However, what we didn’t expect was that the females typically choose the dominant males to copulate with in the earlier days of the season and will often be nesting come the later days of the lekking season. This is what we had found during this visit. We did not see a single hen during this visit.

Because there were no hens to compete for, the males had no heart for the competition. We had very few opportunities to photograph the action we had witnessed during our first visit to the lek two years prior.

The light, however, was spectacular – we had no reason to complain and we all made memorable portrait style photos of these birds booming, dancing and cackling.

Never a disappointment, hopefully this Missouri population somehow continues to hang on so that WGNSS members can continue to enjoy this spectacle in Missouri.

-OZB

I found two juvenile Zone-tailed Hawks on 10/08/16 at Brazos Bend State Park, just west of Houston, TX. I didn’t know until later how rare of a find that it was. Population estimates for the state of TX are around 50 breeding pairs. Also, this species is usually found further west in Texas – this was only the forth recorded observation at this location.

The northernmost breeding blackbird of North America, the Rusty Blackbird unfortunately has the distinction of being in one of the steepest population declines of all N.A. bird species.

Rusty Blackbirds nest throughout the boreal forests of Canada and Alaska, but winters throughout the eastern United States in areas including wet forests near permanent bodies of water. They will also utilize agricultural environments. Among the protected areas considered important for overwintering habitat is Mingo NWR, located in south-eastern MO.

Rusties exhibit an interesting variability in plumage throughout winter and spring, as can be observed in the different birds photographed in this post. Males are dressed with varying amounts of the rusty warm color that gives this species its name. This coloration is located on the tips of newly emerged feathers during the molt. As these fine feather tips wear and break off, the males will become primarily black and luminescent in summer breeding plumage. Female Rusties are even more interestingly plumaged, with tans, browns and blues.

Different survey methods, such as the Breeding Bird Survey and Christmas Bird Count all suggest that the Rusty Blackbird population has declined by more than 90% over the past three decades. Reasons for this decline are not well understood, but are likely to include the acidification of wetlands, loss of wetland habitat in general, loss of forested wetland habitat on wintering grounds and poisoning of mixed-species wintering blackbird flocks in south-eastern United States, where they are considered as agricultural pests.

In his book Birder’s Conservation Handbook – 100 North American Birds at Risk, where much of the information in this post was collected, Jeffry Wells suggests the following actions to address the population decline of the Rusty Blackbird:

-OZB