The year 2024 was a very notable year in our area. No, I’m not talking about the circus joke of an election coming up. Of course, I’m referring to the year of the Brood XIX periodical cicada emergence. Brood XIX, also known as the “Great Southern Brood,” holds a special place as a natural marvel. These periodical cicadas are a part of the Magicicada genus, known for their unique life cycle, which spans 13 years, culminating in a synchronized mass emergence.

Unlike annual cicadas, which appear every year, periodical cicadas have a distinctive life cycle, emerging in massive numbers after spending 13 or 17 years underground. These insects belong to three distinct species groups, with Brood XIX being part of the 13-year group that is comprised of four species: Magicicada tredecim, M. tredecassini, M. tredecula, and M. neotredecim. Cicada broods are geographically isolated populations that emerge in synchrony, making their appearance not only rare but region-specific. Brood XIX has a vast range, covering at least portions of 11 states across much of the southeastern United States.

Life Cycle of Brood XIX

The life of a Brood XIX cicada is primarily hidden underground, where they live as nymphs, feeding on sap from tree roots. For 13 years, they remain underground, quietly developing and maturing. Then, seemingly overnight, millions emerge from the soil in an overwhelming display of nature’s rhythm. Once they emerge, their primary purpose is reproduction.

Adult cicadas live only for a few weeks. During this time, males produce loud, buzzing mating calls using specialized structures called tymbals. These mating calls fill the air, creating a chorus that can reach deafening levels in regions with high cicada density. After mating, females lay eggs in tree branches, and once the eggs hatch, the nymphs fall to the ground and burrow into the soil, starting the 13-year cycle anew.

The Mystery of Synchronized Emergence

One of the most intriguing aspects of Brood XIX is the synchronized nature of their emergence. The question remains: how do they know it’s time to come out? Scientists believe cicadas track environmental clues, such as soil temperature, to time their appearance. When the soil reaches about 64°F (18°C), it signals that it is time for the cicadas to surface.

The reason for their long, synchronized life cycles is believed to be a survival strategy known as predator satiation. By emerging in overwhelming numbers all at once, they reduce the likelihood of being completely eaten by predators. There are simply too many cicadas for predators to consume, ensuring that enough survive to reproduce.

Additionally, 13 and 17 are both prime numbers and this is not likely a mere coincidence. Because these intervals are in prime-numbered years, it is nearly impossible for these patterns to overlap with the breeding strategies of would-be predators.

The Ecological Importance of Cicadas

Though their emergence may seem disruptive, periodical cicadas play a vital role in the ecosystem. Their sheer numbers provide a feast for predators, from birds to mammals, and their death leaves behind nutrient-rich carcasses that fertilize the soil.

While some may find them a nuisance due to their loud calls and vast numbers, these insects do not pose a significant threat to crops or forests. Their presence is fleeting, and they leave behind a healthier environment in their wake.

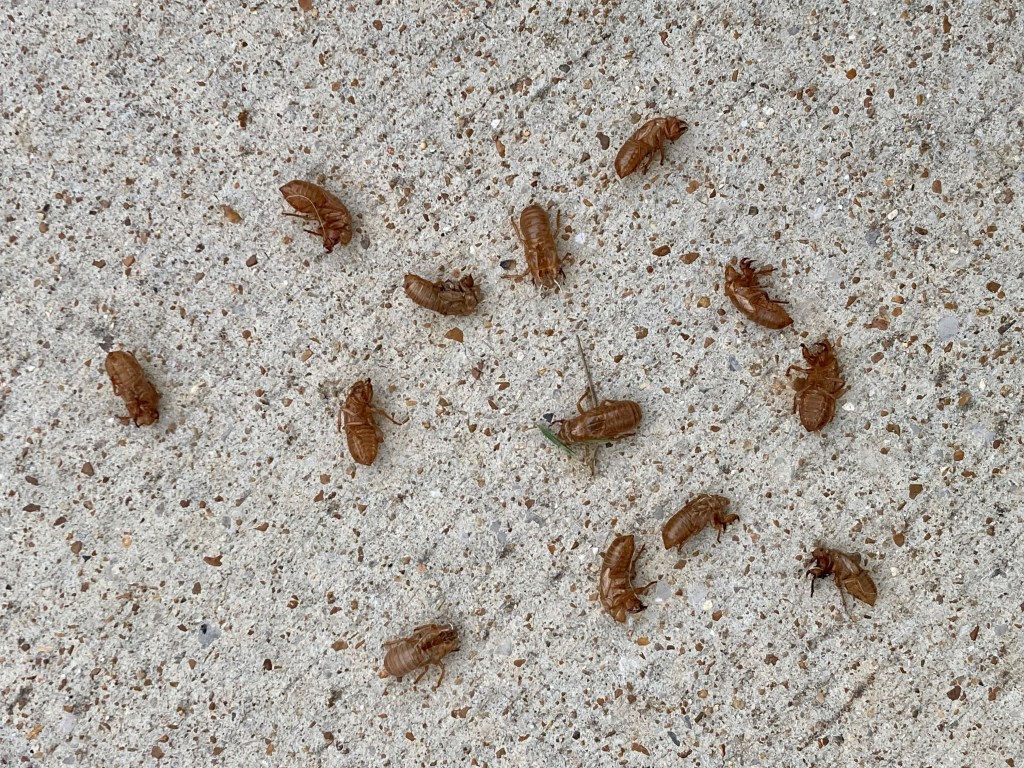

Of the millions of cicadas that emerged in our neighborhood, many had issues with expanding their wings as shown here. These individuals become likely calories for others and will not be able to pass on their genes to the next generation.

That thin line…

I’m sure you’ll agree that anyone with a shred of curiosity about the natural world would find what I shared here of immense interest. As a naturalist, I am still overwhelmed by what I observed for a few weeks in May in our suburban St. Louis County neighborhood. I spent many hours in amazed observation, watching them climb as freshly emerged adults, listening to their midday chorus and observing as my watch counted more than 100 decibels standing in our front yard.

As mentioned above, it is true that in the grand scheme of ecology, these creatures provide nothing but benefit – except, if you are a young woody plant. This is where I found my my awe and fascination becoming replaced with a red, searing rage. For those who may not know, I have spent considerable time, effort, and money over the past four years planting approximately 50 trees and bushes in our once florally depauperate yard. The spring and early summer of 2024 were turning out to be absolutely perfect in regards to establishing woody plants. Temperatures were mild and rains were plentiful.

Then I slowly realized the numbers of cicadas emerging in our neighborhood and the pressure my plants were soon to receive from the thousands of ovipositing females that were looking for just what my yard provided. The ovipositors of the female cicada are sharp and literally metal-studded. These guys are as apt as beavers when working with wood. Heavy pressures from swarming periodical cicadas can and do kill young trees. Cicadas love young trees for depositing their eggs because there are plenty of branches that are the perfect size — about the diameter of a pencil. They especially love young trees that are exposed to the full sun. This makes tremendous evolutionary sense. A young tree that is in full-sun will typically have all the advantages for growing and will therefore more likely be around for the full 13 years that it knows its offspring will need to feed on its host’s roots. I will never forget shaking young dogwood trees in the front yard and watching as hundreds of cicadas swarmed off of them, most simply flying for 50 feet or so and turning right around to land in the same tree.

An example of the pressures of the Brood XIX cicadas on the young and establishing trees in our suburban yard.

Over the next month or so I watched as limb after limb on most of my trees browned and succumbed to the damage done by the heavy onslaught of ovipositing females. I filled several trash cans with limbs that were either self-pruned or that I removed once they were certainly dead. No tree in my yard has died at the time of my writing this, but most plants were significantly set back in their efforts in becoming established. I will have to wait and hope that most will make it through the coming winter season.

Magicicada neotredecim ovipositing on branches of Cotinus obovatus (American smoke tree).

I made a list of the 26 plants I recorded that were used for ovipositing by the Magicicada cicadas in our yard. With a couple of exceptions, this list comprises every woody species in the yard. I even recorded them ovipositing in the herbaceous forb, Penstemon digitalis.

List of plants used by ovipositing Magicicada Brood XIX cicadas in a St. Louis County yard in 2024 eruption.

Amelanchier arborea, Amorpha fruticosa, Aronia melanocarpa, Asimina triloba, Carpinus caroliniana, Cephalanthus occidentalis, Cercis canadensis, Cornus florida, Cotinus obovatus, Diospyros virginiana, Euonymus americanus, Euonymus atropurpureus, Gymnocladus dioicus, Hamamelis virginiana, H. vernalis, Lindera benzoin, Nyssa sylvatica, Penstemon digitalis, Physocarpus opulifolius, Prunus americana, P. serotina, Quercus bicolor, Q. muehlenbergii, Q. shumardii, Sassafras albidum, Viburnum dentatum

Of the plants listed above, particularly high preference seemed to be for the redbuds, dogwoods and oaks. I’m not sure if there is really some taxa preference or if these particular plants simply had more of the best sized limbs.

With hopes of photographing the full cicada lifecycle, I collected quite a few stems from trees that were dropped due to the damage they received or that I removed myself. Unfortunately, my insect rearing skills need some work and I never did see a newly emerged cicada nymph. I did cut into some branches and photographed the eggs.

Eggs from Magicicada sp cicada that were inserted into the pith of Amorpha fruticosa stems. Up to 30 eggs may be inserted in each incision the female makes in the plant and a single female may lay up to 600 eggs in her life.

The next generation…?

Despite the angst and dread this caused when wondering what would become of my woodies that I have spent so much time in watering and protecting from deer over the past several years, I was very pleased to live in a place that still had natural wonders such as this. If the damage caused to my trees indicates the potential success of the next Group XIX emergence, then I am happy and will look forward to the next time we see these guys, assuming I am fortunate enough to be here in 13 years. Hopefully enough of my trees will survive to help them on their way.