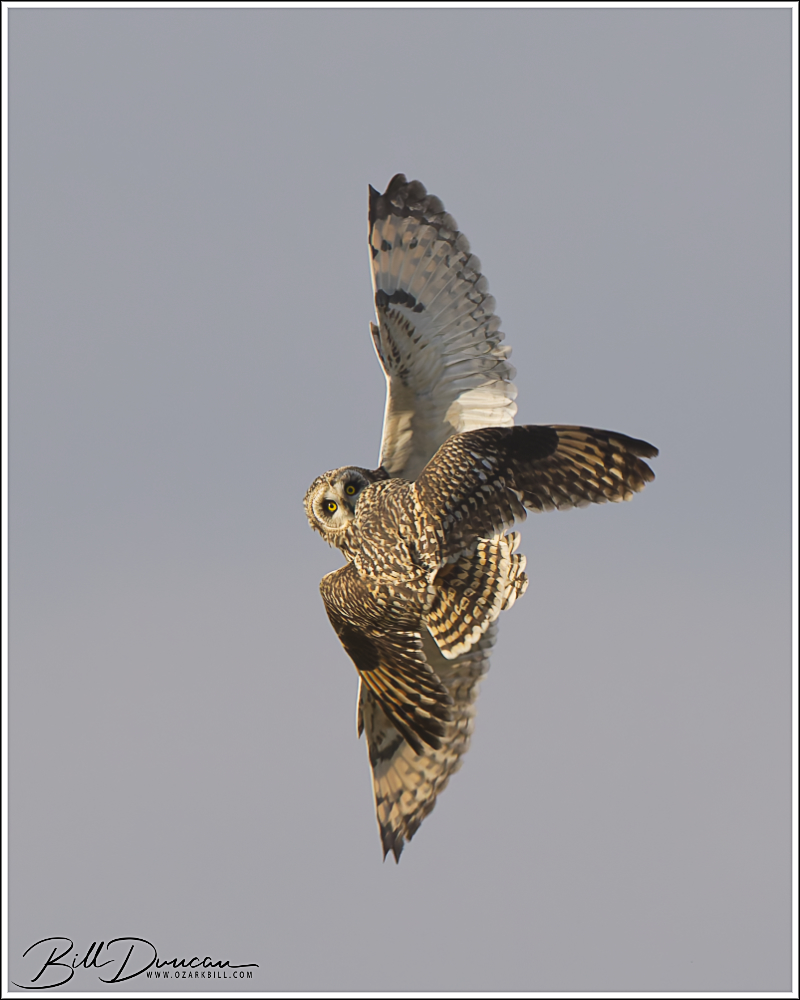

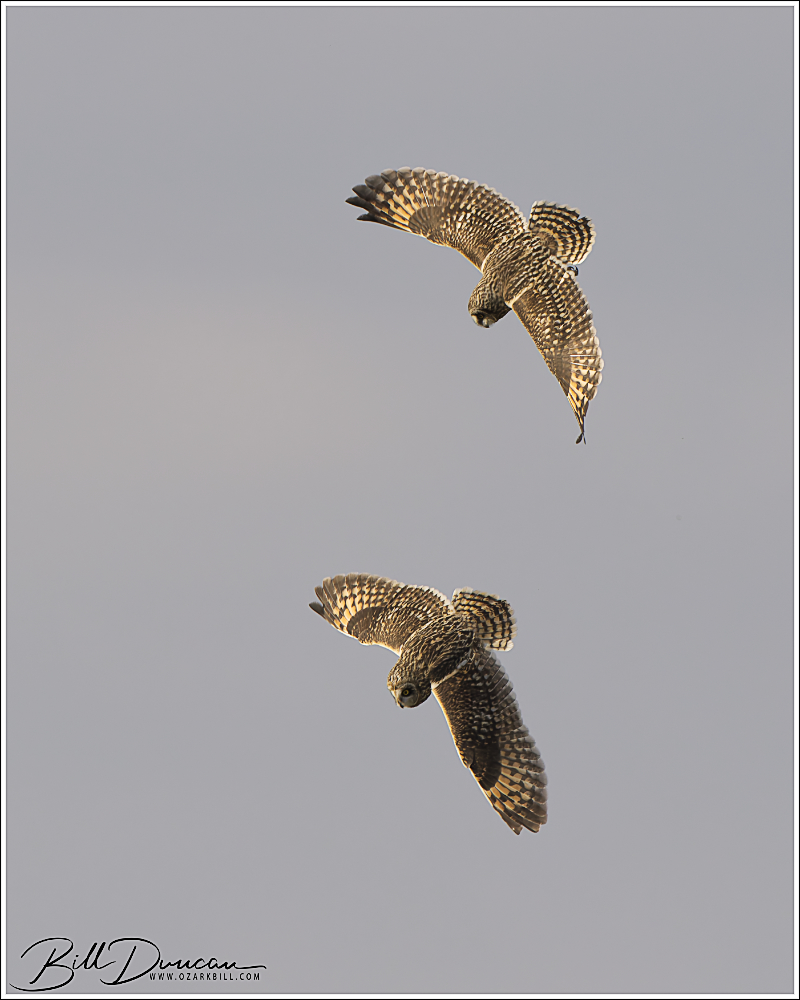

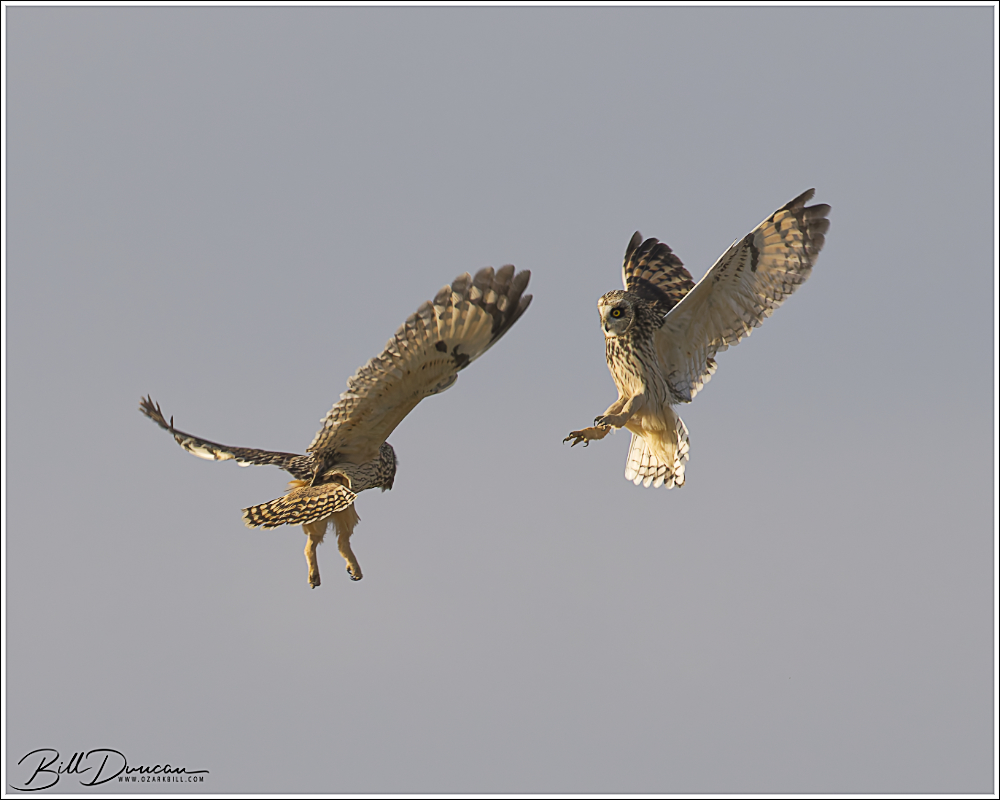

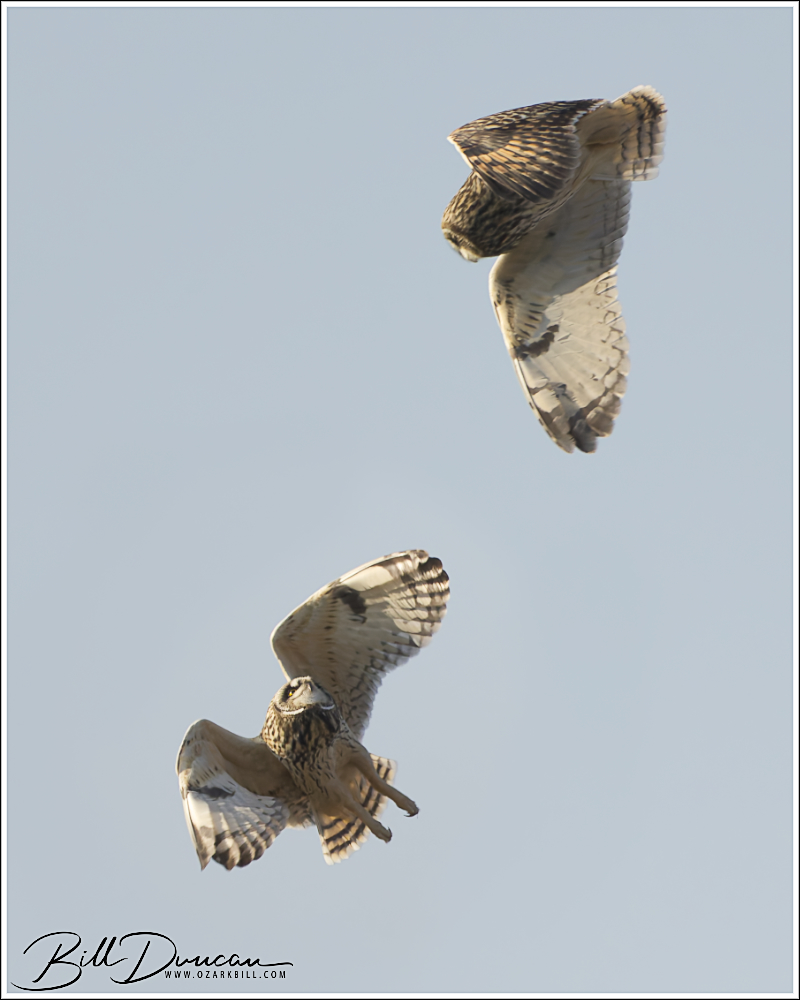

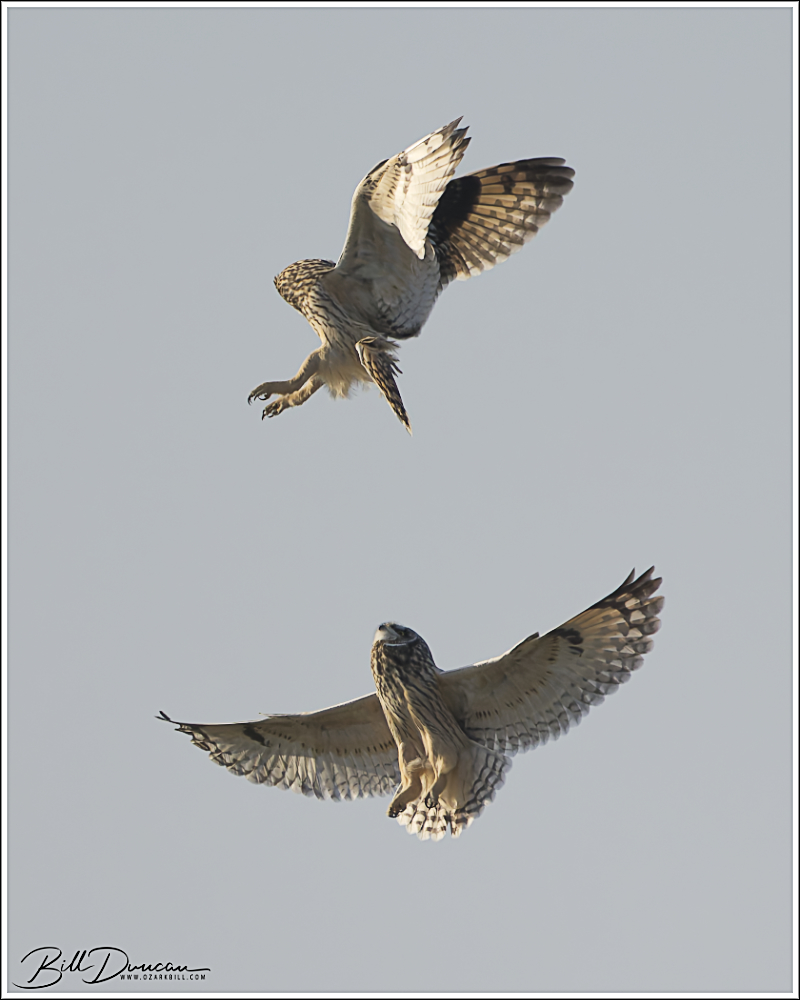

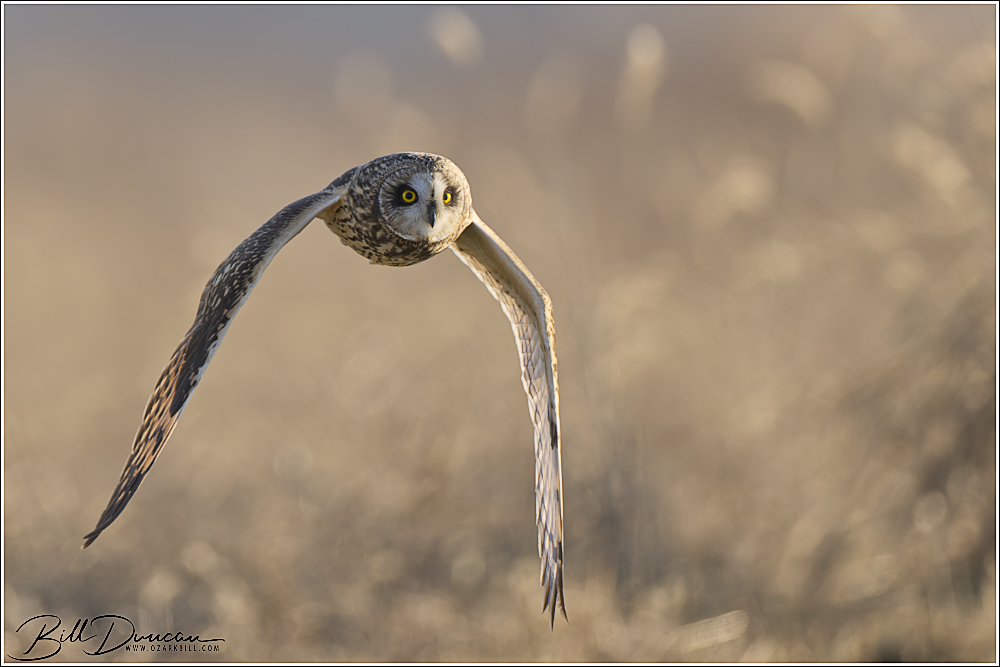

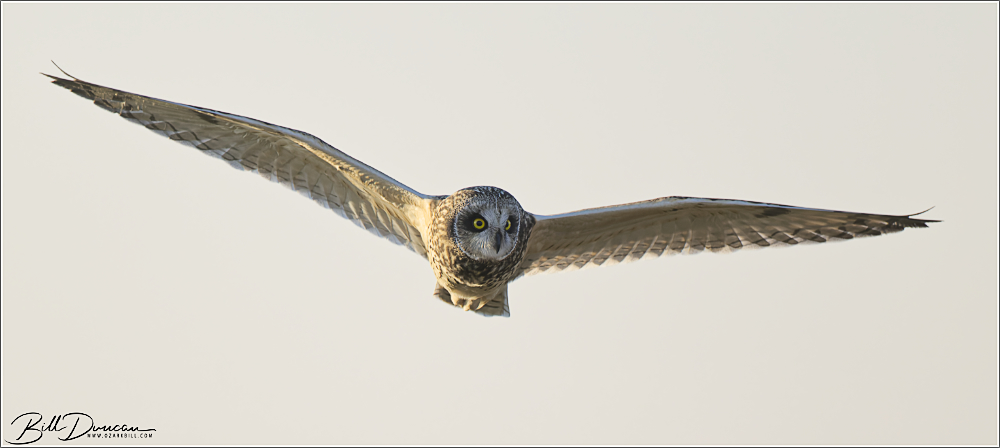

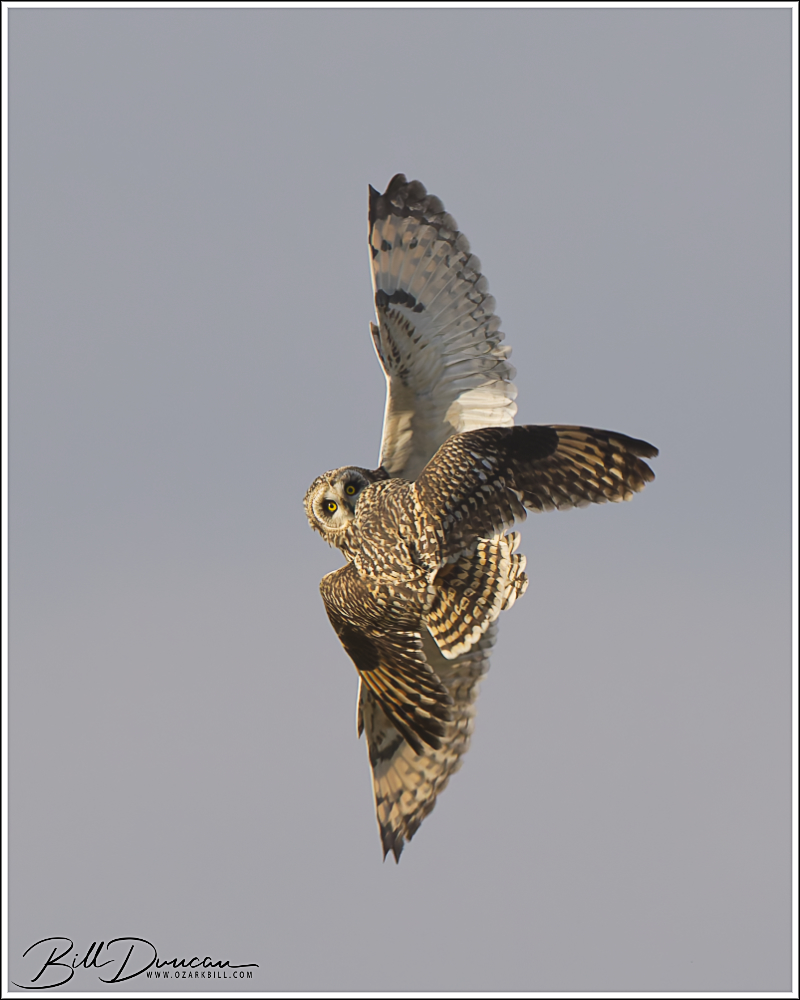

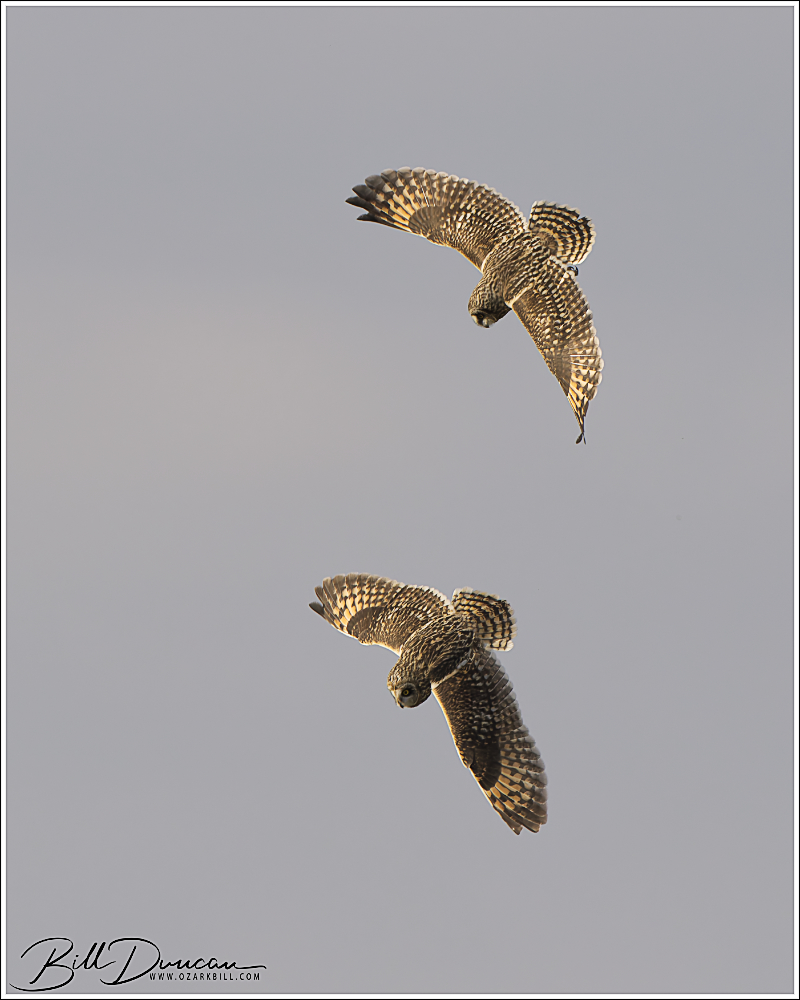

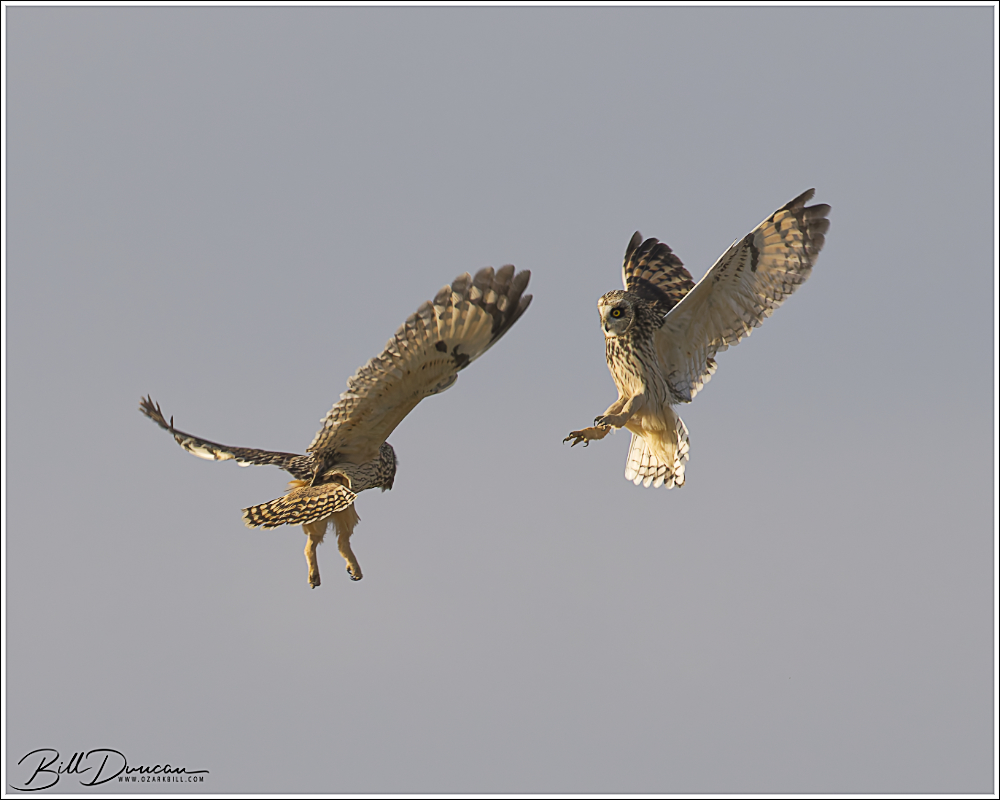

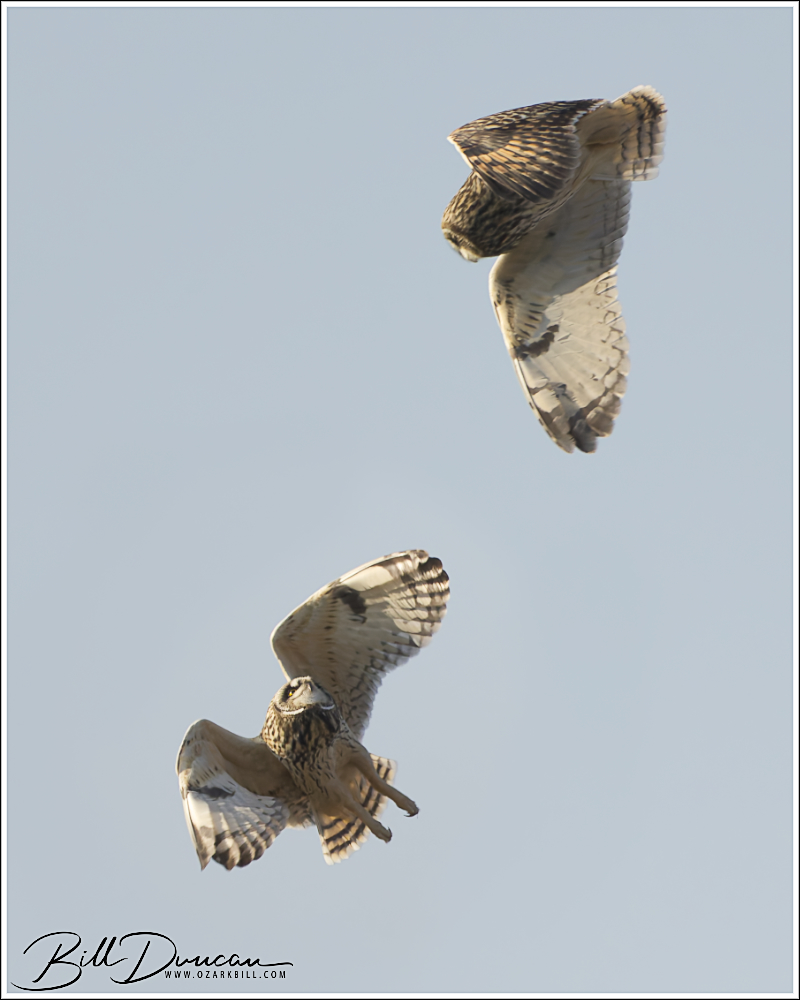

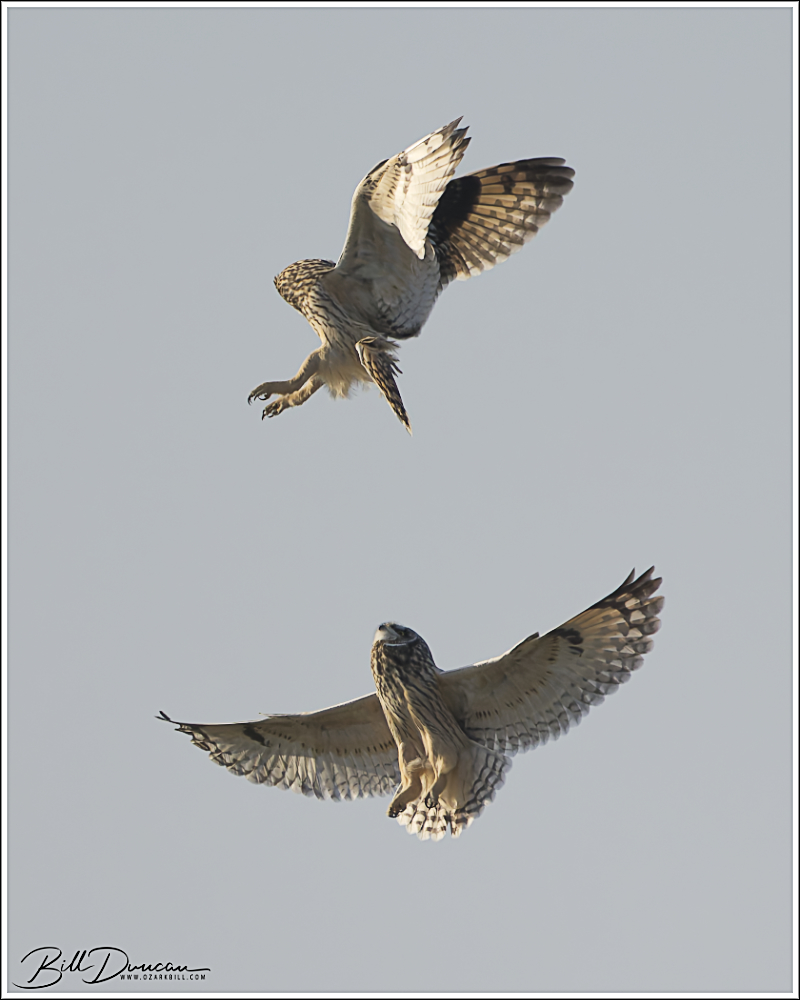

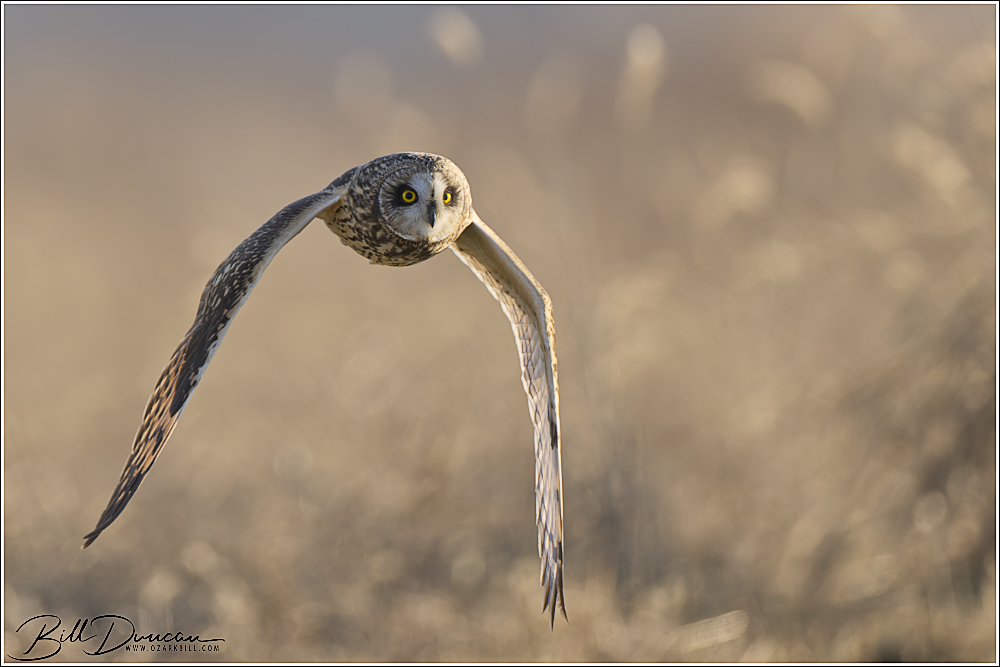

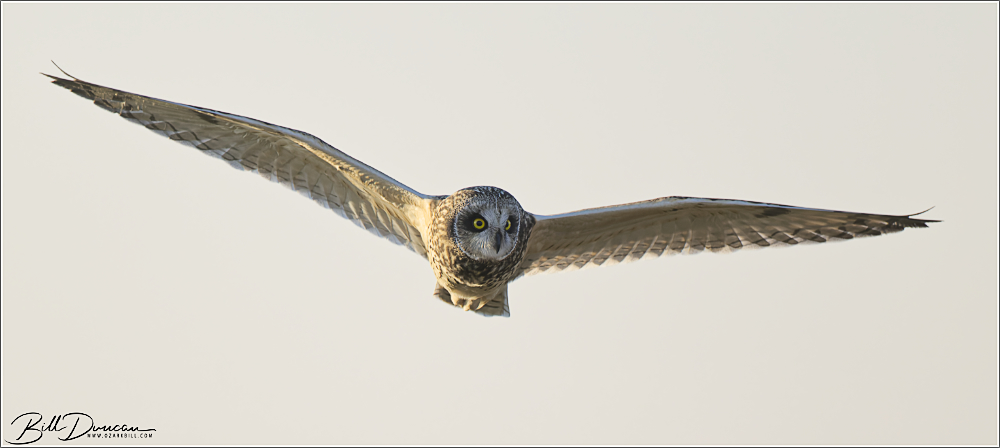

Here are some of my favorites from a couple trips to a new-to-me Short-eared Owl location in southeastern Illinois.

"What a thousand acres of Silphiums looked like when they tickled the bellies of the buffalo is a question never again to be answered, and perhaps not even asked." -Aldo Leopold

Here are some of my favorites from a couple trips to a new-to-me Short-eared Owl location in southeastern Illinois.

The Webster Groves Nature Study Society’s (WGNSS) Nature Photography Group headed to the LaRue Pine Hills in mid-October to visit the famous LaRue Rd, better known as the “Snake Road.” Our targets for the day were snakes, of course, along with any other herps that we could be fortunate enough to find. Unsurprisingly, the snake of the day was the cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus), of which we found close to 15 individuals. We found several different frog species and a real good number of cave salamanders (Eurycea lucifuga).

Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus)

A short ways from the main road, we came across a small grotto. Looking closely with a light, I was able to find at least five cave salamanders resting on different shelves. After about 15 minutes on my knees, working out how to best light and photograph these guys, I finally focused my attention towards the back end of this small cave. There I noticed a medium-sized cottonmouth with its head raised that was apparently watching me the entire time, about a foot or so behind the salamanders.

We were joined by our friend, Stacia Novy, on this trip, who provided an unexpected treat! She brought along her two Aplomado Falcons that we had an opportunity to photograph, pet, and watch eat. Unfortunately, strong winds and a few soaring Bald Eagles that would not leave the area limited the amount of flight time the birds had, but we really appreciated the opportunity.

A couple photos of Stacia with her bird

Afterwards, the group headed to one of my favorite breweries – Scratch in Ava Illinois. Stacia brough one of the Falcons to the outside location and we had a most unique partner to go along with our wood-fired pizzas and beer.

Back in early June of this year, the WGNSS Nature Photography Group travelled east to Pyramid State Recreation Area in Perry County, Illinois. Here we met with Stacia Novy, a wildlife biologist working with Southern Illinois University. Stacia’s goals are to find and identify grassland bird species nests, collect morphometric, embryonic and maturation data on eggs and nestlings, and to document fledging and depredation rates. Stacia is a true professional and she took care in how we approached nests and got our photographs. She finds dozens of nests each year and collects important data used for conservation and habitat management decisions.

Approximately 60% of all of North America’s grasslands have been destroyed due to agriculture and other development purposes. Unsurprisingly, grassland species in general are the most at risk birds from this loss of habitat. The numbers of these obligate grassland species have declined by 40% since 1970.

Due to high incidence of predation, grassland bird species must be quite careful about where and how they place their nests. Stacia showed us the types of vegetation different species like to use and how they attempt to camouflage their nests. It takes a lot of work and diligence to find these nests and we appreciated Stacia sharing some of these with us.

Here are some of the photos I took with my cellphone of some of the species we were fortunate to be able to see.

Prothonotary Warbler photographed at Pyramid State Recreation Area, IL.

I took another trip recently to Carlyle Lake and had a blast photographing these American White Pelicans. There were far more than 1,000 of these giant birds, coming and going from the dam’s spillway.

A couple of friends and I went to visit some sand and gravel hill prairies in central Illinois yesterday. Although it is a delight to visit those places and their unique floral communities, we didn’t find a lot to make us pull out the cameras. We took a short break from walking through the prairies in near perfect weather for an August day and did a little cat hunting in the nearby Sand Ridge State Forest. Along with some hungry mosquitos we happened across this cute little one feeding on a species of red oak. This is the silk moth Antheraea polyphemus. This species is among the largest caterpillars to be found in our area, but this guy was pretty tiny. I believe this is a 2nd instar.

On a couple of successive Saturdays in mid-February, I had the pleasure to find myself at an old favorite spot to practice my high-speed action photography on some of the cutest little predators that I can imagine. In a spot more popular with fisher folk, I setup immediately behind the spillway of the Carlyle Lake damn with high hopes of shooting the Bonaparte’s Gulls that winter in this area.

On my first Saturday visit, these cute little “Bonnies” represented at least 75% of the gull species taking advantage of the stunned gizzard and threadfin shad that come pouring through the spillway. This was great! Although photographing Ring-billed Gulls is always good for practice, they don’t excite me very much at all. What wasn’t great on this first day was the light, which I would describe as something like the sloppy end of a morning’s constitutional. Thank goodness for modern cameras with much improved high ISO performance and autofocus systems!

Photographing Bonnies while hunting like this is a real test of a photographer’s skills and their photographic gear. These guys are faster than a prairie fire with a tailwind. They have to be with the ever present Ring-billed Gulls nearby waiting to steal an easy meal.

The photos I’ve shared so far all showed adult winter-plumaged Bonaparte’s Gulls. First-year winter birds are east to distinguish from the adults with their black tail bands and “M”-shaped black markings on their wing tops. These first year birds are every bit the skilled fishers that the adults are as you can see below.

On my next visit a week later, the skies were clear and I was now challenged with a pretty strong mid-day light coming into the spillway. I felt that this still should afford more speed and a bit better image quality than I had on my previous visit. Unfortunately, the Bonnies must have moved elsewhere. Most of the gulls present were Ring-billed and I only counted four Bonnies during the hour or so I was there.

Wildlife photographers looking for a fun and fast-paced challenge that has no chance of interfering with their photographic subjects should really consider visiting this location.

-OZB

Miguel and I were offered a very special treat back in April when our new friends and gracious hosts, Rick and Jill, offered to show us a very unique and amazing animal, the Illinois chorus frog (Pseudacris illinoensis). The Illinois chorus frog is a species of study for Rick and his students, who are hard at work trying to document the life history and ecological details of this species of conservation concern. Existing in only a handful of counties scattered across Illinois, Missouri and Arkansas, this frog is classified as G3, meaning it is vulnerable to extinction. The primary forces causing the decline of this species is land development, primarily from agriculture.

The Illinois chorus frog requires sandy wetlands. These types of areas are being lost due to drainage efforts for agriculture. The scattered remnants of these habitats are increasingly becoming isolated, likely limiting geneflow between pocketed populations.

The natural history of this species is incredible. Due to the quick draining nature of their preferred sandy habitat, these frogs spend 90% of their lives below ground. Their breeding season typically begins in February, where they take advantage of water from icy thaws and early spring rains to breed in ephemeral pools. By May, the frogs have buried themselves in underground tunnels that they dig with muscular forearms. Unlike most other frog species that spend large amounts of time in subterranean environments, the Illinois chorus frog is known to feed, eating worms and small invertebrates.

Organizations like the University of Illinois, Illinois Department of Natural Resources and the Heartland Conservancy are doing a lot of work in a number of places to discover more about their ecological needs and protecting and managing habitat these frogs need.

Another great thing Rick and Jill showed us were Illinois chorus frog tadpoles that were in artificial breeding “ponds” that were setup for them. As the hundreds of tadpoles we saw suggest, they were doing really well here.

I’m still excited about being able to see and photograph these wonderful frogs and hope to visit them again during an early spring.

OZB

Ever since seeing the photo of Disonycha discoidea in Arthur Evans’ “Beetles of Eastern North America,” I have been wanting to find and photograph this gorgeous Chrysomelid. I have looked for years for this species around St. Louis and southeastern Missouri, and even planted one of its host plants, Passiflora incarnata, in our yard hoping to possibly attract them.

Just a couple weeks ago, my friend, Pete, posted a bunch of picks from his botany trip to southern Illinois on Facebook. As I perused through his collection of fascinating plants he found, I stopped at a photo of several beetles that were on a grape vine. In this photo was a single D. discoidea. Getting a little upset, I messaged Pete to see if he could tell me exactly where he had found this. He was at Giant City State Park and because of smartphone technology, he forwarded me his geotagged photo and I had access to exactly where he had taken the picture.

However, I knew this was a big risk and I didn’t get my hopes up. First, Pete had taken his photo approximately a week before Sarah and I took the 2.5 hour drive south. In addition, the beetle he photographed was on a grapevine, not their typical host plant. Was this just an accidental occurrence of this beetle or could they use grapes as an alternative host? Nothing in the literature suggested that this occurred with this species; apparently, it is monophagous and only uses members of the Passiflora to feed.

We decided it was worth the drive. Giant City State Park is a high quality area and I knew that if we struck out we wouldn’t have to try hard to find something else of interest. We found Pete’s spot of original find pretty easily and started searching. After a couple hours of looking as hard as we could among the grape and poison ivy we decided we weren’t going to find the species there. Utilizing smartphone technology again, I thought it might be a good idea to look for Passiflora plants that had been documented in iNaturalist within the park. My phone signal was pretty poor, so we drove to one of the highest points we could find and I found a single spot that had these plants documented.

These plants were found in a poor scrub prairie habitat along with blackberry and even more poison ivy. We started looking, finding and searching between 50 and 100 of these short plants. We looked very closely and I had a chance to try my DIY collapsible beat sheets that I made over the winter. No luck. I couldn’t believe it. I really thought we had a good chance. We knew the species had been found in the park and here we were within a sizeable population of the host plants. You’ve seen the photos already, so obviously we found our target. And, of course, insect finder extraordinaire, Sarah, was the one to find the beetle on a ragged, half-eaten P. incarnata plant. I immediately got to work photographing from a safe distance. One of the reasons they call them flea beetles is that they will jump great distances upon being disturbed. Ultimately, we found four individuals all on the same plant. Thankfully, this species is quite large for a flea beetle and I didn’t need to get too close that higher magnifications would require.

So what’s up with that coloration?

This species exhibits aposematism, also known as warning coloration. This is the same reason that unpalatable or downright toxic species like monarchs and milkweed bugs along with stinging predators like yellowjackets or velvet ants show warning colorations. Disonycha discoidea picks up cyanogenic glycosides from its Passiflora host plant, making it distasteful or toxic to would-be predators. By evolving this aposematism, the insects can advertise this and avoid the predators that would be on the lookout for an easy meal. In the tropics, a group of butterflies known as the heliconiines also acquire these toxic compounds from the larval feeding on Passiflora.

It was great to finally find this target species. The larvae of this species is also quite photogenic. If I find the time to make a return visit this summer, I would love to find a few of them as well.

Thanks for stopping by!

OZB