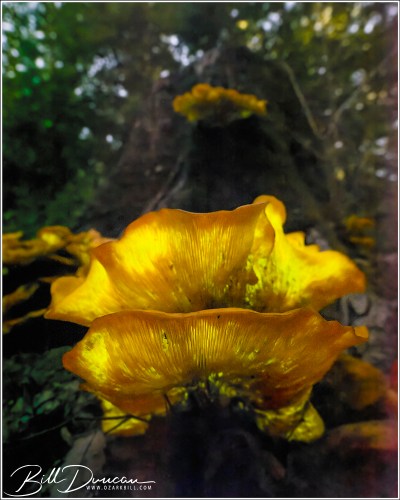

I have long waited to find and photograph the eastern jack-o’-lantern mushroom (Omphalotus illudens). With as dry as this past summer and autumn have been, this has been a terrible year for finding mushrooms of most types. So, I was quite surprised when Pete Kozich sent me a photo showing a large bunch O. illudens growing around a dead hardwood stump at a nearby location in St. Charles County. We arrived shortly after the beginning of astronomical night in order to be able to capture the bioluminescent glow that this species is well known for.

The pale yellow-green bioluminescence, colloquially known as “fox fire,” is only found in the lamellae (gills) of fresh mushrooms. We were somewhat disheartened when we arrived, finding the majority of the group to be well past their prime. Thankfully, there were still a few caps that were fresh enough that we could perceive the glow with our dark-adapted eyes and with the camera.

Bioluminescence in the Fungi kingdom is quite rare. Of the approximately 100,000 described fungi, only 71 species have been reported expressing this trait, all within the Order Agaricales, or gilled mushrooms (Stevani et al., 2013). The cause of the bioluminescence in fungi is due to the activity of the enzyme luciferase working on its substrate – luciferin. The selective advantages of concentrating these compounds around the gills of the mushrooms are not exactly known, but it has been hypothesized that light emitted from bioluminescent fungi attract nocturnal arthropods that may aid in the wider dispersal of spores (Oliveira et al., 2015). Pete and I noticed a number of insects, namely craneflies (Tipuloidea), which were hanging around the gills of the fresh mushroom caps. Whether the bioluminescence or the rotting mushrooms surrounding these caps were the primary bait drawing these insects, I can only speculate.

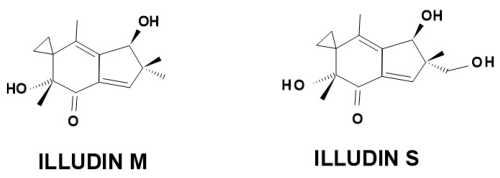

Although these mushrooms slightly resemble and smell as wonderful as a basketful of sweet chanterelles, the jack-o’-lanterns are not too be eaten! This species produces the sesquiterpenes – illudin S and illudin M, chemical compounds formed as secondary metabolites in the fungus . The illudins are quite toxic and will make one extremely sick when eaten. There is an upside found here, however. Illudins are known to be antineoplastic and are now being used in the development of anti-cancer drugs.

Photographing O. illudens can be a challenge. These are best photographed when fresh caps with exposed lamellae are present. A night around the new moon would be most optimal. The two photos shown here, depicting the bioluminescence, were taken with the following camera settings: ISO 3200, f/4, and 5-minute exposures. In retrospect, I probably exposed these for too long. The bioluminescent glow would have been better emphasized with a bit darker of an exposure. These might look as though they were taken with some sunlight or artificial light source, but I can assure you it was very dark with only the light from a near-full moon.

Another thing I wish I would have thought of doing is to collect a cap or two and brought them home to photograph in a perfectly dark room. In doing this, the only light available would be that from the glowing mushroom. Ah well, we now know of a good stump that houses this fungus. With luck, we can try again next season a bit earlier and try this again.

Happy Halloween!

REFERENCES

Oliveira A.G., C.V. Stevani, H.E. Waldenmaier, V. Viviani, J.M. Emerson, J.J. Loros, J.C. Dunlap. Circadian control sheds light on fungal bioluminescence. Curr Biol. 2015 Mar 30;25(7):964-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.021. Epub 2015 Mar 19.

Stevani, C.V., A.G. Oliveira, A. G., Mendes, L. F., Ventura, F. F., Waldenmaier, H. E., Carvalho, R. P., & Pereira, T. A. (2013). Current status of research on fungal bioluminescence: biochemistry and prospects for ecotoxicological application. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 89(6), 1318-1326.